Each year, the Bonn “intersessional” falls midway between the annual conferences of parties (COPs), held in November or December, where ministers arrive to hammer out political disagreements.

This year’s intersessional is particularly important as December’s COP24, in Katowice, Poland, must finalise the Paris “rulebook”—the operating manual the deal needs when it enters force. However, after slow progress in Bonn, negotiators agreed to another week of talks to be held in September in Bangkok.

Bonn also marked the opening of the Talanoa Dialogue. This allows countries to informally take stock of progress towards the Paris Agreement’s goals, without any sense of judgement.

Permeating the meeting, though, was the perennial question of finance for developing countries, as they struggle to cope with the impacts of climate change and mitigate further warming. Another continuing talking point was the impact of the US’s intended withdrawal from the agreement.

Paris rulebook

The Paris “rulebook” was the most substantive issue for the talks. This practical and technical operating manual is needed to implement the Paris Agreement and will guide questions such as what climate pledges should look like and how financial support should be tracked.

This complex work is spread across three negotiating tracks and multiple, closely linked “agenda items”. The UNFCCC has a lengthy progress tracker on its website and published a concise list of tasks at Bonn.

“

Substantively, they have made quite a significant amount of progress but [there is] quite a lot more to do. There’s no drama that there’s an extra session. It’s just hard.

Camilla Born, senior policy adviser, E3G

Most of the work falls to the Ad-hoc Working Group on the Paris Agreement (APA). Its agenda items are shown in the table below and include climate pledges, transparency of action and support and the 2023 global stocktake.

| Agenda Item | What it covers | What it means |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Climate pledges | What parties should include in their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and whether guidance should be common to all or split into differentiated versions. |

| 4 | Adaptation reporting | How parties should communicate their adaptation efforts. |

| 5 | Transparency | How parties should report on action they take, progress they make and support they give to others, including climate finance. |

| 6 | Global stocktake | How parties will take stock, in 2023, of collective progress towards the Paris targets. |

| 7 | Compliance | How compliance with the Paris Agreement will be monitored. |

| 8 | Other business | Issues raised include climate finance and the Adaptation Fund. |

The technical bodies of the UN climate convention, SBI and SBSTA, are also responsible for parts of the Paris rulebook, in particular, accounting for climate finance (see below).

Each part of the rulebook made progress at Bonn. Nevertheless, hopes of leaving with a single negotiating text fell flat, forcing parties to agree an extra week of talks in Bangkok, to take place the week of 3-7 September. Camilla Born, senior policy adviser at green thinktank E3G tells Carbon Brief:

“Substantively, they have made quite a significant amount of progress…but [there is] quite a lot more to do.…There’s no drama that there’s an extra session. It’s just hard.”

In total, working texts across all the issues still run to hundreds of pages.

Climate pledge guidance is one of the trickiest items, with a post-COP23 summary of positions running to 180 pages. A 34-page “navigation tool” agreed at Bonn to focus debate has no formal status and contains a “wide range of strongly-held views”. The 180-pager remains on the table.

One key issue is whether the NDC guidance should cover mitigation alone, or also adaptation, climate finance and loss and damage. Another is whether there should be two sets of guidance for developed and developing nations, or universal rules with allowances for differentiation.

Naoyuki Yamagishi, WWF Japan’s lead on climate and energy, tells Carbon Brief:

“NDCs are the foundation of the Paris Agreement, [so] the negotiations to give ‘guidance’ to NDCs naturally suffer from the hard lines taken by parties.”

China, India and others argue for two sets of rules, with a recent Indian proposal suggesting historic responsibility for climate change be used to differentiate. The EU, US and Japan are among those arguing for single guidance applying to all parties and for NDCs to be quantifiable.

Turkey and others argue against quantifying all pledges with metrics, such as absolute emissions reductions. It says that pledges should be “nationally determined” in form, as well as content.

Separate negotiations continue, under SBI, on common timeframes for NDCs. Options include five years, 10 years, or a rolling “5+5” of firm plans and indicative targets subject to review.

There was more progress on the first of the five-yearly global stocktakes in 2023, where parties will track progress as part of the Paris ratchet mechanism to raise ambition over time.

Working text runs to just 14 pages, though parties disagree on how long the process should take and whether it should focus on themes, such as mitigation and adaptation, or on the three goals of Article 2 on adaptation, finance flows and temperature limits.

The stocktake will be divided into three phases: preparatory information gathering; technical review of inputs, possibly measuring collective progress; and a political review of findings before agreeing a summary, a political declaration agreed by all parties, or a final statement from the meeting.

One difficulty is that the inputs to the stocktake depend on other parts of the rulebook. The graphic below illustrates this complexity, showing how the Paris transparency framework – where current working text runs to 67 pages – interacts with other parts of the deal.

Links between the Paris Agreement transparency framework and other parts of the deal. Image: World Resources Institute.

Roundtable discussions before Bangkok will discuss how to manage these interlinkages.

Talanoa Dialogue

Bonn also hosted the first session of the Talanoa Dialogue, the Fijian presidency’s spin on the “facilitative dialogue” agreed in Paris as a way to ratchet up still-inadequate ambition. The year-long “storytelling” process has three questions: where are we?; where do we want to go?; and how do we get there?

The Bonn climate change conference, 6 May 2018. Image: IISD/ENB | Kiara Worth.

Parties and others, including companies and NGOs, could submit stories to an online portal ahead of Bonn. At the talks, more than 300 participants in six parallel discussions shared around 700 stories.

“

Talanoa, let us not forget, is really the first stocktake after Paris, so the Fiji presidency should be commended for putting in place an innovative format that generated a lot more dynamism than might have been the case otherwise. But it was a reality check of where we are and it’s clearly not where we need to be.

Paula Caballero, global director of climate programme, World Resources Institute

Many were encouraged by this novel format, which aimed to create a non-judgemental space to listen and build trust, in contrast to the often fraught political and technical discussions.

Paula Caballero, global director of the climate programme at the World Resources Institute (WRI), tells Carbon Brief:

“Talanoa, let us not forget, is really the first stocktake after Paris, so the Fiji presidency should be commended for putting in place an innovative format that generated a lot more dynamism than might have been the case otherwise. But it was a reality check of where we are and it’s clearly not where we need to be.”

Others caution that the outcome of the dialogue is unclear. Sébastien Duyck, senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), tells Carbon Brief:

“The Talanoa Dialogue went well, but there is no clear vision about how [it] will ‘land’ politically. For many parties, it is crucial to turn this storytelling exercise into a strong political mandate for parties to enhance NDCs.”

The next step is for the stories shared so far to be gathered into a synthesis report ahead of a high-level political phase at COP24. The deadline for submissions is 29 October.

Loss and damage

Loss and damage has become a perennial issue at climate talks. This is the need to address climate impacts locked in by past emissions and for which adaptation is not possible. It is mentioned in the Paris Agreement, but is not formally part of talks on the Paris rulebook.

Talks centre instead on a lower-level technical process called the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM). This has struggled to move forward, particularly on raising finance to tackle the problem.

Last year, countries agreed to create more space for the topic at a one-off session in Bonn called the Suva expert dialogue. This gave countries the chance to volunteer views on how to minimise and address loss and damage.

It was also seen as a step towards the 2019 review of the WIM, set to take place at COP25.

Harjeet Singh, global lead on climate change at Action Aid, says one clear message was that insurance is not a “silver bullet” to tackle loss and damage. For example, insurance doesn’t work for slow-onset events such as sea level rise, where some damage is certain. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Developed countries kept talking about insurance, [but] what we need is different kinds of instruments.”

He adds that developed countries hardly participated in the discussions, with only Germany actively addressing finance for loss and damage.

“Developed countries have not engaged and that was quite a dampener, because we fought so hard and we really wanted it to be a dialogue.”

Discussions will continue in September at a meeting of the executive committee of the WIM. Also relevant is the meeting next week of the UNFCCC’s “Task Force on Displacement”, which will produce recommendations for COP24 on the displacement of people due to climate change.

Pre-2020 action

One major source of tension at COP23 last year was the need for richer countries to ramp up action before the Paris Agreement enters into force in 2020.

Developing countries are frustrated that the Doha Amendment still has not been formally triggered. This will extend the Kyoto Protocol on developed country emissions out to 2020. Only 109 countries have ratified the amendment, short of the 144 needed.

The $100bn target for annual flows of climate finance is also seen as a key pre-2020 commitment.

A high-level dialogue on pre-2020 action will be held at COP24. This formal stream for discussions meant the subject received less attention at Bonn, E3G’s Born suggests. She tells Carbon Brief:

“I think there were also behind-the-scenes confrontations between parties to work out what pre-2020 action actually looks like: you have the $100bn, you have changes in emission targets. But that’s just not going to happen, really, so what else is it going to look like?…The only countries left to ratify [Doha] are middle-income and developing countries, so that doesn’t really satisfy the pre-2020 politics because a lot of it is [the need for] developed countries to show that they are doing more.”

Climate finance

Finance is always an important and thorny topic at the negotiations and this latest meeting in Bonn was no exception. Some countries say they will not support a “package deal” in Katowice without progress on finance.

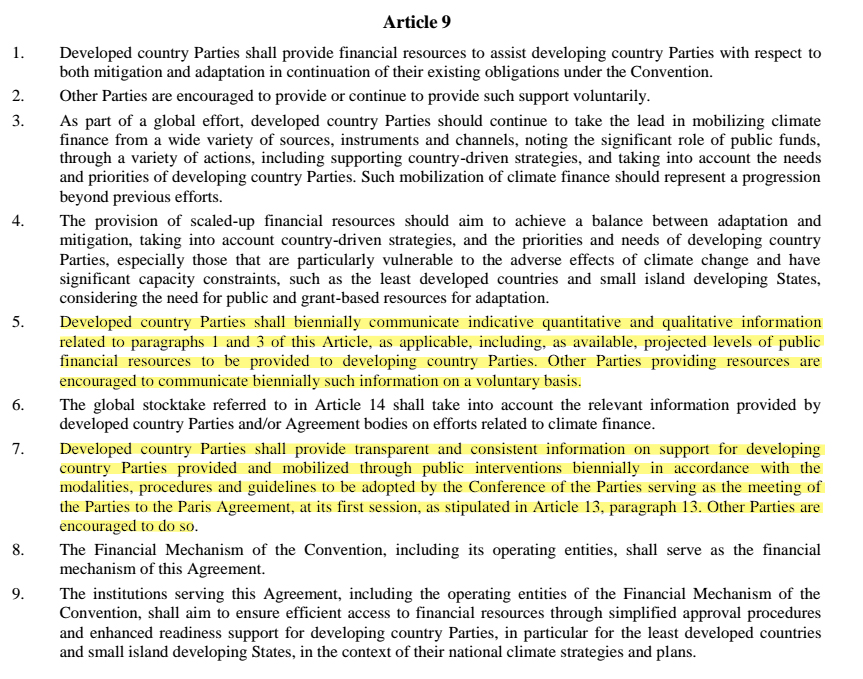

There are several ongoing strands of discussion, all of which made limited progress at Bonn. One covers reporting on future flows of finance from developed to developing countries, mandated by Article 9.5 of the Paris Agreement.

Progress at Bonn was captured in a 17-page informal note, with talks set to continue in Bangkok.

Talks on Article 9.7, covering how to report past financial flows, produced a 62-page informal note. Eddy Pérez, policy analyst at Climate Action Network Canada, tells Carbon Brief there was “slow progress”.

Bonn also discussed the Adaptation Fund, a small multilateral fund established under the Kyoto Protocol. This is politically significant because it only funds adaptation projects. After much debate at COP23 last year, countries agreed that the fund will also “serve” the Paris Agreement.

However, there are many technical details to iron out due to differences between Kyoto and Paris. These include how to manage the transition to the Paris regime, who will be able to access funds and how they will be governed. A 16-page informal note sets out the options.

Also under discussion was the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the main vehicle for climate finance. The GCF is supposed to be replenished once it has allocated 60% of its pledged resources.

This will be an important chance for developed countries to increase climate finance, says Pérez. At the current rate of project approval, the trigger is expected to happen later this year. However, the fund still needs to figure out its approach to replenishment. There is also the unavoidable fact that Donald Trump has said he will no longer allow the US to be a GCF donor.

Another issue is the 2025 climate finance goal, which the Paris Agreement says must be set before 2025 at a higher level than $100bn in annual flows promised by 2020. Pérez tells Carbon Brief talks are currently more about the process for this new goal rather than setting a concrete number.

Bringing all these different strands of finance discussions together, Pérez adds:

“The important thing to understand is that…there is a linkage, something that glues all of [the different finance discussions] together, which is the need for developed countries to send signals that they are going to provide support.”

Carbon markets

Another issue on the agenda was Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which includes voluntary use of “internationally traded mitigation outcomes” (ITMOs)—effectively carbon credits.

Progress was once again slow and negotiators depart Bonn with a series of informal notes totalling 54 pages on credits, the market mechanism and non-market approaches. A key cross-cutting disagreement is how much guidance, rules and supervision are needed, if any.

Jos Cozijnsen is a legal consultant on emissions trading who has been following this process. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The risk now is that the lowest denominator decides what will happen and that’s not enough, because you need good rules for high quality carbon markets.”

In this case, Cozijnsen says those pushing for stronger rules—such as the EU and small island states—could pursue international market mechanisms outside the Paris process.

Looking ahead

Eyes now turn to the COP24 deadline for finalising the Paris rulebook. Before then, the co-chairs of the rulebook negotiations have been tasked with drafting a series of “tools” by 1 August. These will effectively be new versions of the working documents parties have been haggling over in Bonn.

The co-chairs should suggest streamlined text and ways for parties to reach “an agreed basis for negotiations”. In other words, a formal negotiating text. They must do this without removing any options on the table. However, parties rejected the option to explicitly ask for draft text.

However, some observers argue the co-chairs have leeway to draft bits of negotiating text, if there is informal support from parties. Yamide Dagnet, project director on international climate action at the World Resources Institute, tells Carbon Brief:

“The wording…means the co-chairs have a lot of latitude to produce helpful or adequate materials to land a negotiating text by the end of Bangkok. [This] could include examples of negotiating texts.”

The rulebook co-chairs, with the chairs of the subsidiary bodies, are also tasked with writing a joint “reflections note”, by mid-August, setting out progress so far and ways to move forward.

Alden Mayer, director of strategy and policy at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), said in a statement:

“Sharp political differences remain on a handful of issues, especially on climate finance and the amount of differentiation in the Paris Agreement rules for countries at varying stages of development. These issues are above the pay grade of negotiators in Bonn, and will require engaging ministers and national leaders to resolve them.”

Meanwhile, there are a series of high-level climate meetings over the coming months, shown in the table, below. These meetings offer space for informal conversations to continue ahead of COP24.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 22-24 May | Clean Energy Ministerial, hosted by the European Commission and Nordic countries |

| 8-9 June | G7 summit under the Canadian presidency |

| 16-18 June | Petersberg Dialogue, hosted by Germany |

| 20-21 June | Ministerial on Climate Action (MoCA) convened by the EU, China and Canada |

| 17-21 September | Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) meeting on loss and damage |

| 3-7 September | Additional climate talks in Bangkok, Thailand |

| 12-14 September | Global Climate Action Summit in California |

| 18-30 September | UN General Assembly and Climate Week, in New York |

| 8 October | Launch of IPCC Special Report on 1.5C |

| 30 November - 1 December | G20 summit under the Argentinian presidency |

| 3-14 December | COP24 in Katowice, Poland |

Securing a robust rulebook is widely seen as vital to the success of Paris, yet its complexity is compounded by a perceived lack of political leadership. In contrast, heads of state—notably from the US and China—staked political capital on securing agreement in Paris.

While the US team has continued to engage constructively in negotiations, it is unlikely to lead from the front when it comes to the crunch political phase.

Logistics around the small host city of Katowice could be a more mundane factor in the success of the COP24 talks. Concerns centre on balancing busy schedules with the need for sleep, as many hotels are reportedly more than an hour from the conference venue.

Finally, the UK is reportedly keen to host COP26 in 2020, another key year when countries must present new or updated climate pledges. Turkey and Italy have already expressed interest in hosting the meeting.

This article was republished from Carbon Brief.