A vacuum cleaner, a hair straightener, a laptop, Christmas lights, an e-reader, a blender, a kettle, two bags, a pair of jeans, a remote-control helicopter, a spoon, a dining-room chair, a lamp and hair clippers. All broken.

It sounds like a pile of things that you’d stick in boxes and take to the tip. In fact, it’s a list of things mended in a single afternoon by British volunteers determined to get people to stop throwing stuff away.

This is the Reading Repair Cafe, part of a burgeoning international network aimed at confronting a world of stuff, of white goods littering dumps in west Africa and trash swilling through the oceans in huge gyres.

The hair clippers belong to William, who does not want to give his surname but cheerfully describes himself as “mechanically incompetent”. He has owned them for 25 years, but 10 years ago they stopped working and they have been sitting unused in his cupboard ever since.

He sits down at the table of Colin Haycock, an IT professional who volunteers at the repair cafe, which has been running monthly for about four years and is a place where people can bring all manner of household items to be fixed for free. In less than five minutes, Haycock has unscrewed and removed the blades, cleaned out some gunk from inside the machine, oiled the blades, and screwed it all back together. The clippers purr happily.

William looks sheepish; Haycock looks pleased. “I wish they were all that simple,” he says.

Today, the repairers will divert 24kg of waste from going to landfill and save 284kg of CO2. Some items can’t be fixed on the spot – notably a hunting horn split in two, which requires soldering with a blow torch – but very little needs to be thrown away.

Gabrielle Stanley, who used to run a clothing alterations business, says she was drawn to volunteering at the repair cafe to combat the “throwaway culture” she sees. “You go into certain stores...” - she throws a dark look - “how they can sell clothes for that price, when I couldn’t even buy the fabric for that much? And then you hear about things that happen [in the factories] in the far east.”

An estimated 300,000 tonnes of clothing was sent to landfill in the UK in 2016 and a report from Wrap puts the average lifespan for a piece of clothing in the UK at 3.3 years.

Globally, the amount of e-waste generated is expected to hit 50m tonnes by the end of 2018. This is partly driven by consumers’ eagerness for new products, but there are also concerns about built-in obsolescence, in which manufacturers design products to break down after a certain amount of time and are often difficult or expensive to fix. In December, Apple admitted to slowing older models of phones, though it claimed it did this for operational not obsolescence reasons.

Repair cafe volunteer Stuart Ward says that when fixing items is actively discouraged by manufacturers, repair becomes a political act. He is vehement about the “right to repair”, a movement opposed to the practices of companies like the machinery company John Deere, which, under copyright laws, doesn’t allow people to fix their own equipment or take them to independent repairers.

“You own your equipment, you’re allowed to take a screwdriver to it and play with it,” he says. “It’s something fundamental.”

Teaching people how to fix their own gear is at the heart of the Edinburgh Remakery, a store on the main street of Leith that is part repair shop, part secondhand store, part repair education centre.

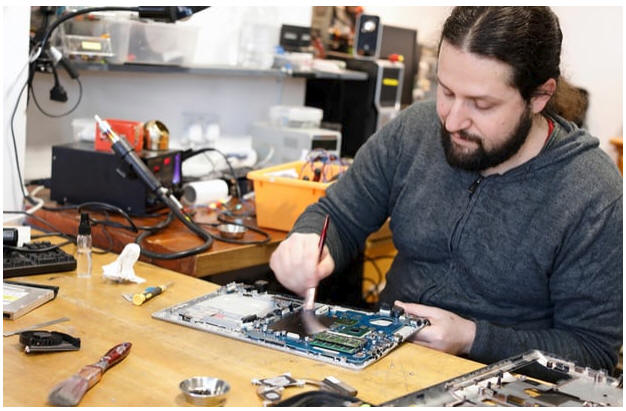

“We do the repair in front of a customer, not out in the back, not hidden,” says Sotiris Katsimbas, the lead IT technician at the Remakery. To do this, Katsimbas and his team conduct one-to-one IT repair appointments for a small fee, as do their colleagues who specialise in sewing and furniture repairs.

“It’s a matter of confidence. It’s not magic. Someone put it together, someone can take it apart, you only need a Phillips screwdriver and some knowledge,” says Katsimbas as he shows Daniel Turner how to open up his laptop so he can clean out the fluff and dust that is causing the machine to overheat.

Since it opened in 2012, the Remakery has diverted 205 tonnes of waste that would have ended up in landfill. But the Remakery is unique in that, unlike much of the repair movement, which is volunteer-led, it is a viable business, employing 11 staff and 10 freelancers. Last year the shop had an income of £236,000 – 30% from grants, 70% generated through sales of furniture and electronics, workshops and repair appointments.

The financial viability of the shop makes it attractive as a model. In the last year, Sophie Unwin, the co-founder of the Remakery in Brixton and the founder of Edinburgh Remakery is setting up the Remakery network to replicate the work internationally.

She has had 53 inquiries from groups interested in setting up similar enterprises in the US, New Zealand, Canada, South Korea, Austria, Ireland, Germany, Australia and elsewhere in the UK.

The network will provide toolkits and advice to groups who want to recreate what she has done in Edinburgh. Unwin hopes that these resources will allow other groups to do in two years what it has taken eight years of trial and error and extremely hard graft to achieve.

For repairers, fixing things is a way of doing something about an obsession with consumerism that Unwin calls “a kind of sickness in society”.

“This is our little attempt to push a little bit in this direction,” says Ward. “To say, we can fix this, we can repair things, don’t give up hope.”