|

| Reviews and Templates for Expression We |

Farming for Nutrient Density – Honour the Microbes and don’t Kick the Cow

Why is it that one carrot just tastes ho-hum and another carrot seems to explode with flavour in your mouth? What’s going on? Aren’t they both just carrots? In short, your ‘wow’ response to the flavourful carrot is your body’s way of telling you to focus on getting more of that item into your mouth.

Flavour is a powerful indicator of the mineral and antioxidant content of food. Flavour sets up a positive feedback loop encouraging us to seek out that produce to more fully nourish ourselves. Flavour tends to equate with nutrient density. Nutrient density is shorthand for foods with high levels of health-giving minerals and complex plant compounds that contain the vitamins and molecules we need for building all aspects of our bodies with nutritional integrity. With the exception of the purposefully addictive, processed variety, food tastes good because it is good for us.

This is in large part why children tend to not like vegetables. Most of the vegetables they are served are flavourless and low in vitamin and mineral content… they lack nutrient density. This is a practical, at-the-dinner-table manifestation of the decline in nutrient density that has rapidly accelerated over the last 100 years. In part, it is a result of massive hybridisation of our commercial seeds, but mostly it’s because of how we are fertilising and managing our agricultural soils. We can turn this around and for the sake of our health we’re best to get on with it pronto. In the New Zealand context it is a precious opportunity to further excel.

Fasten your seatbelts for a brief biology lesson. If you want to change a system wisely, you need to understand how it functions. The element, microbe, plant, energy cycles that underpin agriculture are complex. That’s a good thing. We just need to get a snapshot of how the parts of the ag ecosystem can fit together for optimal quality, production and environmental integrity.

Plants and microbes have a marvellously complex relationship. All plants need some form of microbial assistance in order to access their nourishment and defend themselves. We have to get over our aversion to ‘germs’ and realise that diverse, robust microbe communities are crucial for flavourful, healthy produce and meat. The microbiome is also pivotal for our own gut and mental health. Microbes are our ancestors and we alienate them at our peril. Microbes rule the roost on this planet so we should understand their roles better.

There is an ecological continuum of microbe species from zones populated mostly by bacteria (lava flows and hot pools) where little plant biomass is created, to fungal dominated zones (old growth forests) where plant biomass is the highest. Where we farm and eat is in the zone of about equal numbers of bacteria to fungi in our soils, with a leaning towards more fungi than bacteria when we grow vines, bushes or fruit trees. High fungal numbers are a sign of good soil health and are needed to create humus and long storage carbon in our soils. So, fungi can play an important role in reducing greenhouse gases.

All ecosystems have a tendency to move from bacterial to fungal dominance. Where we, the weather or animals disrupt soil and remove plant cover, the balance shifts toward bacteria and that’s when weedy plants take over. Weeds aren’t inevitable, they’re simply indicators of soil health and nature’s way of trying to re-establish fungal dominance in the soils. Spraying herbicides only makes things worse as fungi are particularly sensitive to ag chemicals.

A particularly important class of fungi to our creation of food with flavour are the mycorrhizal fungi that can set up miles of interconnecting filaments, hyphae, that act like a water and mineral freeway as well as a plant communication internet. Fungal hyphae networks do actually transport compounds between plants that can be 100s of metres apart. These fungi enable mutually supportive, complex relationships between plants of completely different species. The more different species that get connected on this grid, the more productive and resilient those plants will be and the more carbon will be sequestered in the form of humus.

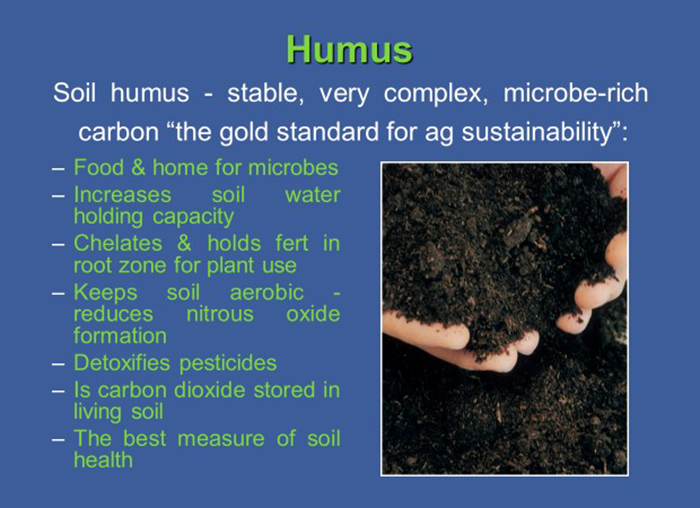

Humus is the world’s most complex molecule. So complex, in fact, that we don’t have a standard test for it and tend to use soil carbon content as a surrogate measurement for humus. However, testable or no, humus formation is the best determinant of ecosystem function and whether we’re headed in the right direction with our soils and ag products. No humus means little mineral storage is occurring, soil is hardening and microbes are malnourished. This means the plants we are cultivating won’t have their minerals delivered to them by microbes in the optimal, colloidal form and thus plants won’t have all the complex building blocks they need for photosynthesis, when and how they need them.

Never underestimate the importance of photosynthesis. Seeing as it is the basis of all life on the planet, we need to ensure that the plants we grow have everything they need to optimize their photosynthetic capacity. Microbes, fungi in particular, are crucial to productive, disease free plants that do lots of photosynthesis. High levels of photosynthesis mean plants have lots of energy and minerals for changing glucose into starches, starches into amino acids, into complete proteins, into fats and ultimately into complex plant secondary metabolites (PSMs).

The reason our food tends to be tasteless is that our plants aren’t getting the proper nutrition they need to do enough photosynthesis to propel their tissues to the optimal creation of PSMs – flavonoids, quercetins, tannins, terpenes and the thousands of other communication, protection and hormone regulation molecules plants can create. These are the plant compounds that deliver what we interpret as flavour. Weirdly enough, these same PSMs are what we need for our tissue building, communication, immune and hormone function. That’s why our bodies jump towards nutrient dense, high PSM, flavourful food when we do taste it. It’s a completely different experience and our bodies know it.

Without microbes in the soil, we’re farming hydroponically and the flavour of most produce makes that clear…no flavour and of little nutritional value to us. As Graeme Sait says, in modern agriculture we’ve bombed the microbe bridge between our soils and the plants we grow. The ‘bombs’ tend to be synthetic inputs in the form of water-soluble fertilisers and ag chemicals. We need to remember that all pesticides/herbicides are ‘cides.’ They are designed to kill. Think fungicide and homicide and then realise that we have the same cell structure as the pests we’re trying to destroy with these chemicals. So is this suicide? Like with weeds, the pathogens and pests are there because we’ve created the conditions to favour them. It doesn’t have to be that way.

Ask yourself, which produce to you tend to pay more for… mainstream ag or organic produce? Clearly, it is possible to farm without synthetic inputs and generally it’s more highly valued in the marketplace. So why, if it’s possible and preferable, isn’t it standard practice?

Mostly it’s because of naivete, commercial interests, ego and paradigm inertia. Farmers tend to assume governments wouldn’t allow ag chemicals on the market if they weren’t safe for us to use, despite them being biocides. Large firms involved in supplying agriculture have their expertise and infrastructure centred around the use of petroleum-based ag inputs. University experts’ prestige and self-worth are based on knowing how to grow foods within a chemical, instead of a microbial, system. And it just takes time, or something catastrophic, to prompt us to see a better way, new opportunities, a different paradigm for food production.

Certainly, there are enough clues of catastrophe out there now with rapid rises in: autoimmune disease, infertility, atmospheric and oceanic carbon dioxide, birth defects, sea levels, mental disorders, erosion, cancer and water pollution. We don’t tend to see them as being related to agriculture but every one of them is. Question is… what does it take to get us to change the way we ‘do’ agriculture and get back to consistently producing flavourful, biocide-free food that fully nourishes, and even heals, us?

Part of the inertia is that it’s more comfortable for us to frame things as simply as possible. It’s simpler when we view agricultural production as a chemical equation: so much phosphorous in the soil minus this amount of phosphorous taken off by the crop equals this much phosphorous needs to be put back into the soil in the form of synthetic fertiliser. Easy but fatally flawed. The clues mentioned above are the wheels falling off the agricultural vehicle we’ve been driving for the last 150 years.

Agricultural ecologies are not a simple system. They are a highly complex one governed by the complicated transactions between plants and their microbes, and we know jack s**t about microbes, actually. A sobering thought which should incline us to view all our ag actions within the framework of “Will this nourish and support microbial diversity and health?”

The good news is, we do know enough now to turn this around and there are numerous examples, here in New Zealand and worldwide, of farmers taking steps to nourish and encourage soil microbe communities, especially fungi. Their results are impressive and heartening with better production, lower costs, less erosion, better flavour and impressive amounts of soil carbon being sequestered.

Biology friendly approaches and techniques have been explored and are being farmer implemented. Some researchers are catching up and beginning to explain how these synergies can happen. And consumers are clamouring for chemical free, environment-friendly, flavourful food. So, what are some principles that we need to observe and techniques to use to regenerate our soil systems? Here are the key ones:

- Institute diverse cover crops into all aspects of agriculture. Don’t let soil be bare. The plants actively feed the microbes they need and that is the basis of all soil formation, structure and fertility. Keep a living root in the soil at all times.

- Back away from synthetic inputs such as petroleum-based ag products (urea and pesticides). Substitute minimally processed fertilisers such as lime, rock phosphates and sulphate forms of minerals. Plants need more than just NPK and with the help of fungi they can access much of what they need from what is already in the soil or in the air.

- Always add a carbon source (humic acids, quality compost, sugars) with fertiliser applications to feed soil microbes

- Keep tillage and soil disruption to a minimum but use ripping or ploughing initially to reverse existing compaction. Use crimpers to create mulches from cover or green manure corps. Use light disking to incorporate crop residues and replant immediately with a wide diversity of seeds. Do NOT use glyphosate based herbicides. Bare soil means dead microbes.

- Farm for humus creation and flavour, neither of which can happen with use of inputs that scorch or poison soil microbes.

- Keep an open, flexible mind and learn to consciously observe what is happening on farm. Inquire into complex plant/ microbe/ soil relationships. Get over being in charge. We’re not. Get a knowledgeable coach who has demonstrated their ability to turn farms around to soil biological diversity and food integrity.

- Embrace complexity. It is the basis of our survival.

Why is this important for New Zealand? Well, we’re far away from our savvy, premium markets that will increasingly be demanding actual verification of our claims to clean, green and the best there is. Just saying we’re great is coasting on our questionable laurels. Soon consumers will have hand held technology for testing food for chemicals and nutrient content. We’re going to have to prove our quality. We can do that, but it involves a change away from the chemical paradigm of farming.

And just a wee public service announcement in defence of cows…they are NOT innately the cause of our water pollution problems. Their urine is harmful only because of the way we’re driving our dairy pastoral systems with urea fertiliser. Our use of superphosphate, herbicides, antibiotics and urea have so altered the soil and rumen microbe communities that they are no longer able to keep nitrogen in its ideal amine form and it converts to nitrate nitrogen, leaching to the waterways and taking precious soil minerals with it. The result is an impoverished soil to which we keep adding ever more synthetic fertilisers to attempt to keep up production.

Great grass growth and per cow production can be achieved at less cost under a regime using non-water-soluble fertilisers. The cows are healthier and the milk quality is better. We actually need ruminants, like cows, to help us sequester atmospheric CO² in pastures through intensive grazing. Our dairy industry could again be the jewel in our crown producing the invaluable fat-soluble Vitamins A, D and K2 and Conjugated Linoleic Acid we need to fully utilise all other minerals and vitamins in our diet.

Cows are important, and while some reduction of numbers on overstocked dairy farms may temporarily be needed for soil recovery, a shift away from dairy or beef raising would be to ignore the most restorative and profitable aspect of our NZ agriculture. Other agricultural countries could grow great fruit and vegetables but most of them would struggle to match our ability to grow green grass all year. Pastoral industries and animal fats are our aces on the world market.

Moving into a biological paradigm for our agroecosystem will ensure we can deliver on the important stuff –

- Humus formation and carbon sequestration that can make NZ carbon negative overall

- Clean water and air

- Absolute best quality, flavourful food that the world clamours for

- Human health and community wellbeing

Is it possible to achieve this zenith of agricultural production with larger scale agriculture? Yes. Do we need it? Possibly not. Our market narrative is better with family farms and modest scale. Diverse well-managed landscapes of modest-sized farms may also be more likely to embody the values and practices of long-term environmental stewardship. What we mostly need is greater awareness and a viable pathway for farmer education that focuses on a new, biology-based paradigm for farming that delivers humus and flavour.

|

|

|

|

Copyright remains with the original authors |