The orangutan is one of our planet’s most distinctive and intelligent creatures. It has been observed using primitive tools, such as the branch of a tree, to hunt food, and is capable of complex social behaviour. Orangutans also played a special role in humanity’s own intellectual history when, in the 19th century, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, co-developers of the theory of natural selection, used observations of them to hone their ideas about evolution.

But humanity has not repaid orangutans with kindness. The numbers of these distinctive, red-maned primates are now plummeting thanks to our destruction of their habitats and illegal hunting of the species. Last week, an international study revealed that its population in Borneo, the animal’s last main stronghold, now stands at between 70,000 and 100,000, less than half of what it was in 1995. “I expected to see a fairly steep decline, but I did not anticipate it would be this large,” said one of the study’s co-authors, Serge Wich of Liverpool John Moores University.

For good measure, conservationists say numbers are likely to fall by at least another 45,000 by 2050, thanks to the expansion of palm oil plantations, which are replacing their forest homes. One of Earth’s most spectacular creatures is heading towards oblivion, along with the vaquita dolphin, the Javan rhinoceros, the western lowland gorilla, the Amur leopard and many other species whose numbers are today declining dramatically. All of these are threatened with the fate that has already befallen the Tasmanian tiger, the dodo, the ivory-billed woodpecker and the baiji dolphin – victims of humanity’s urge to kill, exploit and cultivate.

As a result, scientists warn that humanity could soon be left increasingly isolated on a planet bereft of wildlife and inhabited only by ourselves plus domesticated animals and their parasites. This grim scenario will form the background to a key conference – Safeguarding Space for Nature and Securing Our Future – to be held in London on 27-28 February.

The aim of the symposium is straightforward: to highlight ways of establishing sufficient reserves and protected areas to halt or seriously limit the major extinction event that humanity now faces.

According to one recent report, the number of wild animals on Earth has halved in the past 40 years, as humans kill for food in unsustainable numbers and pollute or destroy habitats, and worse probably lies ahead.

Action is urgently need, say scientists. This point was acknowledged in 2010 at a major international conference in Japan, where governments agreed to establish a network of reserves and protected seas that would, by 2020, cover 17% of Earth’s land surface and 10% of our oceans.

“With more than two years to go, we now have about 15% of land protected and about 7% of oceans,” said one of the London conference’s organisers, Mike Hoffman, of the Zoological Society of London.

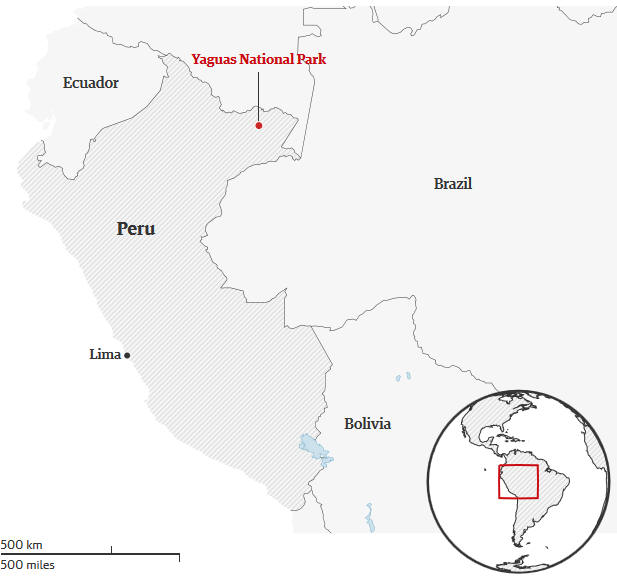

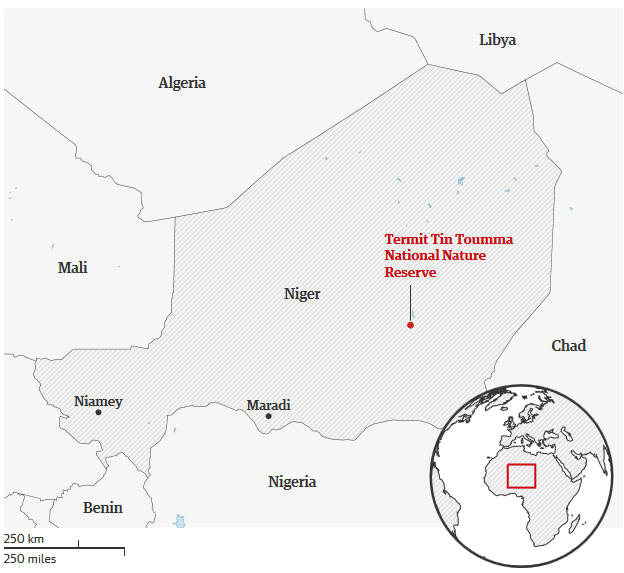

New reserves include the Termit Tin Toumma national nature reserve in Niger, home of the addax antelope and dama gazelle, both critically endangered, as well as the Yaguas national park in Peru, which is known for its manatees, river dolphins, giant otters and woolly monkey.

Hoffman said: “The conference will assess how much these new reserves have helped conservation, examine the problems that have been encountered in setting them up, and look at ways to make further improvements to ensure we meet our target of 17% of land and 10% of ocean protection by the time the next major biodiversity conference is held in China in 2020.”

But many conservationists argue that even if these goals could be achieved, they will still not halt extinctions. The current focus on protecting what humans are willing to spare for conservation is unscientific, they say. Instead, conservation targets should be determined by what is necessary to protect nature. This point is stressed by Harvey Locke, whose organisation, Nature Needs Half, takes a far bolder approach and campaigns for the preservation of fully 50% of our planet for wildlife by 2050.

“That may seem a lot – if you think the world is a just a place for humans to exploit,” Locke told the Observer. “But if you recognise the world as one that we share with wildlife, letting it have half of the Earth does not seem that much.”

The idea is supported by E O Wilson, the distinguished Harvard biologist, in his most recent book, Half Earth. “We thrash about, appallingly led, with no particular goal other than economic growth and unfettered consumption,” he writes. “As a result, we’re extinguishing Earth’s biodiversity as though the species of the natural world are no better than weeds and kitchen vermin.” The solution, he says, is to fill half the planet with conservation zones – though just how this division is to be decided is not made clear in his book. In any case, Hoffman points out, simply setting aside huge chunks of land or marine areas will not, on its own, save the day. “We could earmark the whole of northern Canada as a wildlife reserve but, given the paucity of animals who live in these frozen regions, that would not have a significant effect on a great many species who live elsewhere,” he said.

Locke makes a similar point: “Protecting all of Antarctica would also be an excellent idea and would certainly enhance the percentage of the world that is protected and do great things for life there. However, it would do nothing for tigers, toucans, lions and grizzly bears.”

Simply setting aside half the planet as wilderness and using the other half for giant cities and farms poses other difficulties. Pollution, poaching and climate change triggered by carbon emissions and other human-caused problems would constantly seep from the human half of the planet into the wildlife “zone”.

Instead, conservationists argue, a far more carefully integrated pattern of wildlife areas needs to be established, one that will allow animals to move relatively easily between reserves, and so maintain genetic diversity between populations.

“We need to focus less on simply protecting single, isolated wildlife areas – which are constantly being eaten away at the edges – to more effectively buffer and integrate these core areas into wider landscapes,” says Noelle Kumpel of BirdLife International, which is also involved in next week’s conference.

Such a goal will be tricky because, among many other reasons, animals are no great observers of human boundaries. They move out of protected areas at random and come into conflict with humans.

The problem is exemplified by the wolf, whose numbers have begun to flourish in Europe thanks to the efforts of conservationists. Last month, the first wolf on Belgian soil made its mark by killing at least two sheep, while similar attacks by wolves in France, Germany and Finland have led to demands for culls from angry farmers. Other animals that conservationists have succeeded in restoring in numbers in Europe – such as bears and jackals – have also caused controversy. Integrating humans and wild animals will not be easy.

One solution to be discussed at next week’s conference will be the proposal to make our cities far greener than they are at present. This would reduce the impact of the pollution that they produce, but would also raise public awareness of wildlife issues, according to Daniel Raven-Ellison, a proponent of the creation of “national park cities”.

“London, for example, is a surprisingly green city,” he said. “You would only need to plant on a relatively small amount of extra land to make half its surface green. That would have important ecological effects, but it would also have an important symbolic effect and help raise awareness of the issues we face.”

Citizens of greener cities would be far more likely to engage with nature concerns and would be far more likely to extend their awareness to wildlife elsewhere in the world – to narwhals or turtles or to other threatened species, said Raven-Ellison. “The story of plastics and the oceans provides an example of what cities can do. There has been a real reaction in places like London to the use of plastics which get into the oceans and threaten marine life. As a result, there has been a drive here to have water fountains and use less plastics. Crucially, in cities we can turn up the dial in campaigns like these.”

Other issues will be less easily dealt with, however. Of particularly concern is Africa. The continent is still fairly rich in wildlife, but is expected to change far more drastically than any other part of the world as humanity’s growth continues throughout this century. According to the UN’s most recent population figures, there are around 7.5 billion men, women and children living on our planet, and this is likely to rise to around 11.2 billion by the end of the century – with virtually all of that increase happening in Africa. That continent’s population is expected to swell from 1.25 billion today to around 4.25 billion in 2100. By contrast, population growth in other continents will be relatively low.

The impact will be striking and will come as climate change also takes its toll on the continent’s ecosystems, resulting in considerable international friction. As one observer pointed out: “Africans are not likely to be happy with the non-Africans in the international community telling them where and when they should set up reserves and telling them to halt logging or farming, given the plight they will find themselves in.”

In fact, there are two separate issues at stake with regard to protecting habitats and wildlife for the future, Sir David Attenborough told the Observer. “First there is the moral dimension. We have a responsibility to all these forms of life on our planet because we have power over them.

“However, there is also a practical issue,” he added. “We need to ensure that we have enough life forms on Earth to ensure the planet’s health. But how many is enough? We simply do not know the answer to that question – though I think we should assume that it is a fairly large number and that they need protecting.”

Safe havens

Green turtle

On 18 March 2015, the British government announced a plan to establish the largest marine reserve in the world, around the Pitcairn Islands in the south Pacific. At 834,000 sq km, the Pitcairn marine reserve will offer protection to some of the most pristine waters and coral reefs on Earth, and to a range of endangered species including the green turtle (Chelonia mydas), which is suffering major losses in numbers because of pollution and habitat loss, and from being trapped in fishing nets.

The western hemisphere’s newest national reserve, the Yaguas national park, in rainforest in north-eastern Peru, protects millions of acres of wilderness. Apart from the indigenous people who live there, the Yaguas is home to endangered creatures including manatees, river dolphins, giant otters and woolly monkeys. The park joins a network of reserves recently created to preserve territory in other South American countries including Ecuador, Chile and Colombia.

Addax

The addax – also known as the screwhorn antelope – is one of the world’s most endangered species of antelopes. Only a few hundred remain in the wild, after the species was hunted to near extinction because of its distinctive-flavoured meat. However, the establishment of the Termit Tin Toumma national nature reserve in Niger – where most remaining members of Addax nasomaculatus are concentrated – has raised hopes it can be preserved in the wild along with other endangered species such as the dama gazelle.

Spoon-billed Sandpiper

China has announced a ban on land reclamation in coastal wetlands. In some areas, particularly in the Yellow Sea region, reclamation has caused many bird species to decline dangerously. For example, by 2014, it was believed there were fewer than 228 pairs of spoon-billed sandpipers. The directive falls short of creating protected reserves, but has raised hopes of wildlife being helped to recover there, and that China is now viewing the issue as important.