in 2015, compared to 230 tonnes in 2005. Image: Eco-Business

Almost all of the world’s newly-manufactured plastic ends up as waste or marine litter, when it could instead be used to solve big problems like affordable housing, infrastructure improvement, and sustainable consumer products.

This was the challenge that experts from academia, civil society and the private sector set out to tackle at Australia’s inaugural conference on reducing plastic pollution in Asia Pacific.

Held in Sydney’s Darling Harbour from October 31 to November 1 and organised by advocacy group Boomerang Alliance, the conference brought together some 300 experts from across the plastic value chain to discuss ways to harness the useful properties of plastic—its light weight, versatiity, and low-costs—while mitigating against the harmful impacts that arise when it is carelessly disposed of.

Some 322 million tonnes of plastic materials were produced worldwide in 2015, compared to 230 tonnes in 2005, according to industry group PlasticsEurope. Only about 9 per cent of this was recycled, the rest ending up in landfills—where it can take hundreds of years to decompose—or as marine litter, where it risks being ingested by all forms of marine life, from plankton to seabirds to fish that humans eat.

Denise Hardesty, senior research scientist, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), noted: “In many parts of the world, marine debris can have a significant impact on human health.”

In Ghana, for instance, plastic bags blocked storm drains and flood gates to such a severe degree in 2015 that it resulted in a flood that killed 150 people.

Proper waste management, behaviour change, and designing products so that plastic does not end up as waste are all essential steps for solving plastic pollution, noted Hardesty at the conference, which was co-located with the Plasticity Sydney forum, an event focused on transforming plastic waste into a valuable resource.

Hardesty added: “Solutions lie in us through individual actions, legislative solutions and grassroots efforts. It requires a bottom-up and top-down approach.”

Here are the five most promising strategies that communities, businesses, and policymakers can take to address the plastic waste crisis.

1. Consumers, think different

Hayley Clarke, managing director of recycled products retailer Onya Life, noted that companies can recycle plastic into new products, but their efforts are meaningless if there isn’t consumer demand for them.

The act of buying a product made from recycled plastic materials—whether it is a cup made from post-consumer plastic, swimwear made from recycled plastic drink bottles, or shoes made from recovered plastic—is essential to close the plastic loop, said Clarke.

“If you have the chance to purchase something made from recycled materials, you are signalling that there is a market for it,” she added. “As a purchaser, you have the power to demand change.”

Buying recycled items is not just the responsibility of members of the public, noted speakers. Doug Woodring, director and co-founder of non-profit Ocean Recovery Alliance, added: “Governments and companies can also put requirements for recycled content into their procurement policies.”

2. Build creatively

Whether in the form of unprocessed plastic bottles or shredded waste, discarded plastic makes for an affordable, strong, and versatile building material, speakers at the conference noted.

Onya Life’s Clarke shared the example of Taiwan’s EcoARK building, which is made from 1.52 million recycled plastic bottles; and retail giant Nike’s concept store in Shanghai, which is also constructed entirely out of recycled cans and bottles.

In poor countries across the world, plastic bottles are being used to construct entire homes, noted Clarke, adding that such innovative construction techniques offer a new avenue to recycle plastic waste.

Yet another initiative that repurposes plastic waste into much-needed housing is the NevHouse, an initiative by Australian surfer and entrepreneur Nev Hyman.

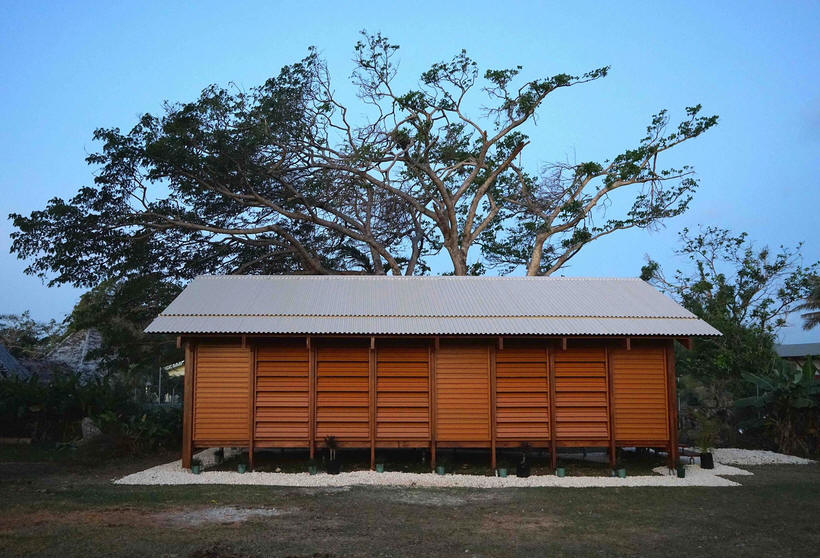

Speaking at the Plasticity Forum, Hyman outlined an effort by his company to build houses in the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu from recycled plastic materials, agricultural waste, and even electronic waste, which has been turned into construction panels.

Each building is strong enough to withstand a category five cyclone, earthquakes, and can be easily washed out because they are made from plastic. This makes them ideal for the climate-vulnerable Pacific Islands, shared Hyman.

A structure can be built in as little as five days, and NevHouse has already made several homes, schools, and clinics on Vanuatu after Cyclone Pam devastated the island in 2015. Hyman added that governments in vulnerable areas can even stock up on recycled plastic panels as a resilience measure, and then rapidly deploy them in the aftermath of a natural disaster.

A NevHouse in Tanna, Vanuatu. Image: NevHouse

“It is a social, economic, and environmental solution to affordable housing,” Hyman explained. “It’s not just about post-disaster relief, but about a sustainable community.”

“

If you have the chance to purchase something made from recycled materials, you are signalling that there is a market for it. As a purchaser, you have the power to create demand change.

Hayley Clarke, managing director, Onya Life

3. Plastic neutrality

Companies from Thailand and Australia unveiled an initiative at the Plasticity forum that could harness the benefits of plastic use while mitigating against the consequences of improper disposal and litter.

The Plastic Neutral Programme by Australian social enterprise Plastic Collective and the Plastic Offset Programme by Thailand-based surfboard manufacturer Starboard are related initiatives that encourage companies to quantify the amount of plastic they use, and the volume of waste they generate. Companies can then offset their plastic use by funding initiatives that help to reduce and avoid plastic pollution.

One initiative they can support is the Plastic Collective’s Shruder, a compact machine that enables communities in remote areas such as regional Australia and the Pacific Islands to recycle plastic waste. By funding the deployment of Shruders with an equivalent capacity to a company’s plastic footprint, firms can call themselves ‘plastic neutral’.

Louise Hardman, chief executive officer and founder, Plastic Collective, said: “It increases consumer confidence, improves employee engagement, and provides a host of other mutual benefits.”

4. Roads and banks

Nani Hendiarti, director of maritime science and technology at Indonesia’s Coordinating Ministry for Maritime Affairs, shared that Indonesia—the world‘s second-largest contributor to plastic marine pollution, after China—takes the issue of marine debris very seriously because “it affects tourism, environment, marine life, and human health”.

President Joko Widodo issued a decree this year known as the Indonesian Ocean Policy, as well as the National Plan of Action on Marine Plastic Debris, which has four pillars. These include driving behavioural change, stopping the leakage of plastic waste into land and ocean ecosystems, and law enforcement.

A key strategy that has helped drive behaviour change in the country is the implementation of Waste Banks, shared Nani. These are facilities located across Indonesia where communities can “deposit” non-organic solid waste such as plastics, and receive a sum of money for their contribution. There are more than 4,000 waste banks in Indonesia currently, and “this approach has the potential to reduce plastic waste and bring about a circular economy,” said Nani.

Yet another strategy that Indonesia is employing to curb the tide of plastic waste is to turn it into roads, shared Nani. Plastic waste is mixed into asphalt, and this strategy results in roads that are cheaper to build, and as much as 40 per cent more durable against high temperatures and rainfall than conventional paths, Nani shared.

There are currently three pilots of plastic tar roads taking place in Indonesia. Other countries such as India have also adopted the solution, and even made it mandatory to use plastic in all new roads.

5. Extended producer responsibility

There are various legislative measures that governments can enforce to ensure that rather than ending up in landfills or oceans, plastic is captured in a cycle of reuse and recycling, experts at the three-day conference noted.

Key among these is extended producer responsibility (EPR). The term, sometimes used interchangeably with product stewardship, refers to a policy where manufacturers must take responsibility for the treatment or disposal of products at the end of their life cycle.

This can be a financial responsibility, such as paying for the retrieval and processing of the waste, or a physical one, such as developing the logistics and mechanisms to collect and recycle waste.

EPR schemes can be mandatory, as with the Container Deposit Legislation that has recently seen a massive rise in adoption across Australia and required beverage manufacturers to pay for recycling drink containers at the end of their life, or they can be voluntary.

Voluntary initiatives launched by the private sector in Australia include Tyre Stewardship Australia, an industry group which aims to develop markets for reusing tyres at the end of their lives, and Soft Landing, an initiative where used mattresses are collected, and their components are recycled into materials such as roof sheeting, carpet underlay, and kindling.

About 60 per cent of Australian mattress manufacturers are a part of the latter initiative, which is currently conducting research and development into how to reuse components such as fabric. The funds for this come from the initiative’s members.

Nick Harford, managing director of sustainability consultancy Equilibrium, shared that these examples illustrate the opportunities that product stewardship presents to drive investment into new technologies.

“There is a business case around product stewardship,” said Harford. “If it is done properly, it can be an efficient and effective way to manage a product through its life cycle.”

“Australian companies have knowledge about how it can be done, and there is an opportunity to export that in Southeast Asia as well,” he added.

Thanks for reading to the end of this story!

We would be grateful if you would consider joining as a member of The EB Circle. This helps to keep our stories and resources free for all, and it also supports independent journalism dedicated to sustainable development. It only costs as little as S$5 a month, and you would be helping to make a big difference.