The common home air conditioning unit has hardly changed since it was first invented a century ago; but researchers in Singapore recently unveiled new technologies that promise more energy efficient and environmentally friendly ways of cooling.

Scientists from the National University of Singapore last week announced the development of a prototype of a sustainable air conditioning unit which uses water instead of refrigerants, and consumes 40 per cent less electricity to operate, and can cool a space to as low as 18 degrees Celsius.

Ernest Chua, associate professor from the university’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, told Eco-Business in a recent interview: “Current air-conditioners are based on technology that is a century old, and there’s not been any breakthrough in making air conditioning less energy intensive or environmentally friendly.”

Statistics from a survey by the National Environment Agency found that air conditioning accounts for almost 40 per cent of electricity bills in the home.

NUS’ prototype of its green air conditioner and the team behind it. Clockwise from top left: Dr M Kum Ja, Dr Bui Duc Thuan, Associate Professor Ernest Chua, and Dr Md Raisul Islam. Image: NUS

Air conditioner manufacturers to date have sought to improve the performance of the machine’s different components such as compressors and evaporators. “But these are marginal improvements. We need to have, as we say in scientific terms, a quantum leap improvement in energy efficiency,” said Chua.

His team has, after four years of government-funded research, produced two new technologies that make it possible for air conditioners to perform cooling functions using water rather than traditional chemical refrigerants.

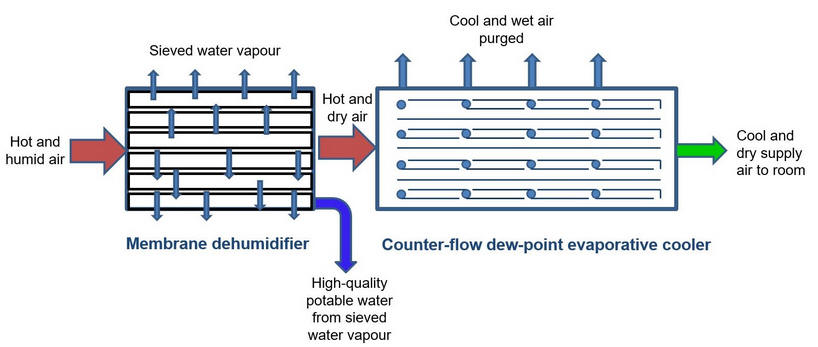

The first is a membrane dehumidifier which uses special water-absorbing materials and a difference in air pressure to extract water from ambient air as it is passed through the membrane. The water removed is potable and almost as pure as bottled drinking water, said Chua.

The drier air is then passed through what is called the counter-flow dew-point evaporative cooler, the team’s second invention. This device removes heat through evaporative cooling, the same process that reduces body temperature through perspiration.

How the National University of Singapore’s new water based technologies work in an air conditioning system. It runs on water instead of environmentally damaging chemical refrigerants. Image: NUS

With the two new technologies, air conditioners no longer need energy-hungry processors or chemical refrigerants to work. Chemical refrigerants, such as the ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) or hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs). CFCs were banned under the Montreal Protocol in 1987, and the Kigali Amendment legally binds signatory countries of the Montreal Protocol to take action against HCFCs.

Refrigerants management is the solution with the most potential to fight climate change, according to Project Drawdown, which ranks climate action in the scale of their impact on climate mitigation efforts.

Instead of relying on HCFCs, the newly developed air conditioner can cool a room using rain water. It needs one litre of water to cool a master bedroom unit for 15 to 20 hours, said Chua. While regular air conditioners expel hot air as a byproduct, the prototype releases humid air that is still likely to be cooler than ambient temperatures.

This helps to avoid disrupting the urban microclimate outside, said Chua.

The world could see an increase of over 1 billion new air conditioners by 2030 as climate change causes rising temperatures and the global middle class gains greater purchasing power. Southeast Asia alone could hit 10 million units by 2018, compared to the 6.5 million units installed in 2013.

The new means of cooling represented by the prototype would not only help conserve energy but also ensure that the environment is not sacrificed in mankind’s quest for thermal comfort, said Chua.

But he emphasised that the 1.6 metre-tall prototype is not the finished version, and his team is now looking to create a more compact and commercially viable product for the market in three to five years’ time.

He estimated that his air conditioner would be 20 to 30 per cent cheaper to produce than models currently available, and last for up to 10 years.

The one drawback is that the team’s technology cannot cool spaces to a low enough temperature to replace the refrigerants-based systems of refrigerators or freezers.

However, Chua said that the new developments could be used in industrial chillers.

Chua was confident that his model is more sustainable than current air conditioners on the market. “Our air conditioning system cannot be any greener, because water cannot be any greener,” he said. “If you find something better than water, let me know.”