|

| Reviews and Templates for Expression We |

'People seem happier': how planting trees changed lives in a former coal community

The National Forest has not only transformed an industrial landscape, it has given people a new sense of belonging and wellbeing, created jobs and boosted wildlife – benefits that could be replicated across the country

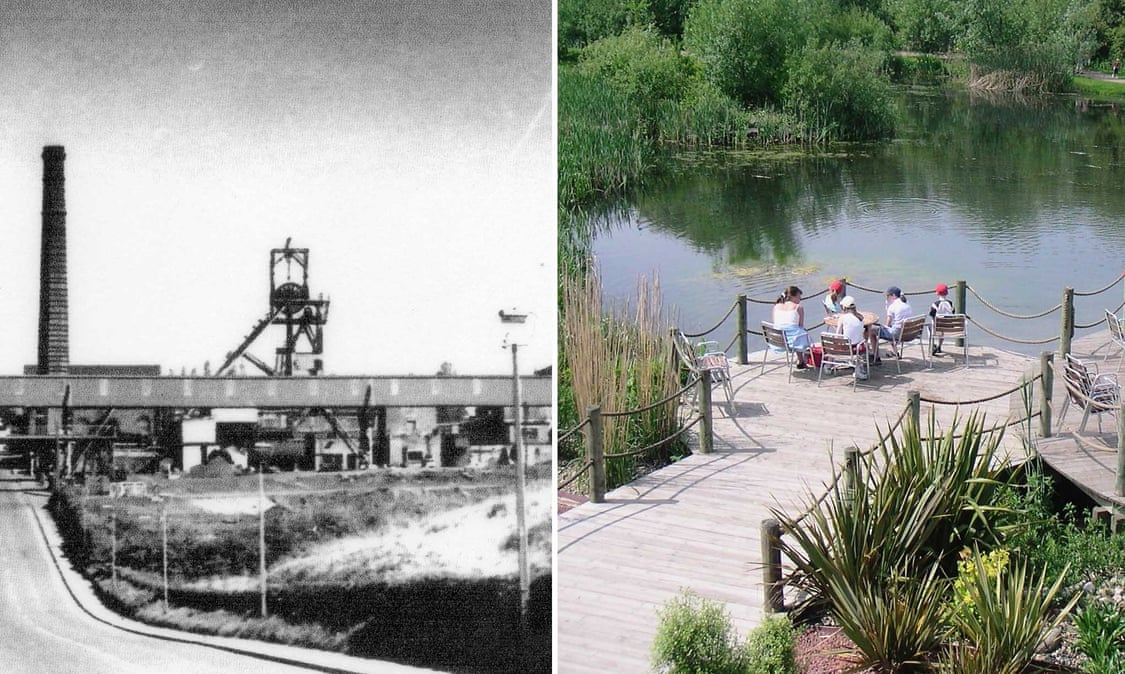

Before and after: the National Forest has given new life to a landscape ravaged by coal mining. Composite: Courtesy of National Forest

Former miner Graham Knight puts his cup of tea down on the cafe table and

looks out through the large glass windows. Trees frame every view; a small

herd of cows meander through a copse of silver birch towards a distance

lake.

“It is quite difficult to put into

words what’s happened here and the impact it has had on people,” says the

73-year-old. “Perhaps the best way to think about it is that people seem …

well, more happy somehow.”

The cafe is in the heart of the first new forest to be created in the UK for

1,000 years, with 8 million new trees stretching over 200 sq miles of

rolling Midlands countryside.

Knight, who worked in one of the area’s many coalmines before they were shut

in the late 1980s, says the forest project has transformed an area ravaged

by the loss of the mines into an increasingly vibrant – and beautiful –

place to live.

“Twenty-five years ago all this was an opencast mine,” he says waving his

hand towards the distant hills. “Mud and dirt with hardly a tree to be seen.

Now just look, people want to live here, they are proud to be from here – it

has totally changed how people feel.”

The first tree in the National Forest was planted more than 25 years ago and

now much of the land that spans Derbyshire, Leicestershire and Staffordshire

is unrecognisable.

![]()

![]()

Move the slider to see how an opencast mine has become woodland.

John Everitt, the chief executive of the National Forest Company which

oversees the project, says the simple act of planting trees has sparked a

dizzying list of spin-off benefits, from tourism to a nascent woodland

economy; from flood management to thriving wildlife; from improved health

and wellbeing to housebuilding and jobs.

“We have embedded trees in and around where people live and made sure they

are accessible rather than as a distant thing that they can visit

occasionally. And we are seeing the benefits in all sorts of ways – and they

are multiplying all the time.”

Everitt, an ecologist by training who has been heading the project for the

past three years, fires off an impressive list of figures to back up his

claims: the forest attracts 7.8 million visitors a year, it has brought

about 5,000 new jobs with hundreds more in the pipeline, woodland industries

from firewood to timber businesses are springing up, craft food and beer

businesses are flourishing and thousands of people cycle or walk the

hundreds of miles of pathways and trails each year.

But he says some of the most important benefits the area has witnessed are

more difficult to quantify.

“People now have a sense of pride in

this place and a sense of belonging and wellbeing. Children who were maybe

nervous of the outdoors are benefitting from being able to walk or cycle or

simply play in the woods.”

As part of the forest project Everitt wants to get a outdoor woodland

classroom and a qualified

forest school teacher into every

primary school to embed what he says is a cultural change in the local

community. There are also

plans for a

woodland festival next summer.

“So far about a quarter of the schools have these in place but soon we want

all of them to offer this. Hopefully this will embed what we are doing in

the next generation … they will learn to cherish it and appreciate what we

have here.”

There is a growing acceptance that trees and access to countryside can

benefit not only the economy and environment but also

people’s

sense of wellbeing

and happiness. This weekend, the environment secretary, Michael Gove, said

the government was committed to planting 11 million new trees in England and

global leaders at the climate conference in Bonn reiterated that trees had a

vital role to play in the fight against climate change. Meanwhile, in

Somerset last weekend campaigners, scientists and policymakers met at a

special tree conference to work out how best this can be achieved.

The scenery at

Feanedock

wood in the National Forest.

Photograph: David Sillitoe for the Guardian

But despite the growing enthusiasm among campaigners and converts, current

tree planting rates across the UK have

fallen to about 6,000 hectares per year – far below the levels

achieved in the 1970s and 1980s which often exceeded 25,000 hectares

annually. Woodland cover in the UK lags far behind large parts of Europe.

Planting rates are now so low in England that they are barely keeping pace

with the amount of woodland being cleared – edging the country closer to a

state of deforestation.

John Tucker of the Woodland Trust said he regularly travels the country

persuading people to plant more trees, pointing out potential spaces on

school grounds, in hedgerows and corners of fields but warned that across

the UK “current planting rates are amongst the lowest for 40 years”.

“There is real awareness of the benefits of trees and woods, and enthusiasm

from landowners and the public to see much more planting. Government

agencies could really help by streamlining approval processes, offering more

advice and simplifying grant aid.”

Back in the National Forest, Everitt says they are doing their bit to

promote tree planting. Although the wood is not one continuous stretch of

trees – there are areas of mature woodland and younger trees mixed with

farmland and grassland as well as towns and villages – roadsides and gardens

have been planted, new housing developments are shielded and framed by trees

and many have new woodland as part of the planning requirements.

![]()

![]()

Move the slider to see how a lake now occupies the site of Hicks Lodge

opencast mine.

Everitt said: “The beauty of this is that we are not planting on land that

has other ecological importance, like wetlands or grasslands or indeed the

best fertile farmland, but there is still plenty of land to go at here.”

Species of animal not seen in the area for decades – such as the otter and

the white hairstreak butterfly – are now taking up residence, and others are

expected to return as the forest matures.

Tree planting has also helped flood management, cleaned up rivers and

streams by preventing “run-off” from farms; not to mentioned the wider

climate benefits of trees capturing carbon from the atmosphere.

As Everitt digs his wellies out of the boot of his car before setting off up

a winding track to inspect another stretch of recently planted broadleaf

woodland, he says all this has been achieved with about £50m of public

money.

“To put that in perspective,” he adds, “it is the same as it would cost to

build about a two-mile stretch of your average three lane motorway.”

|

|

|

|

Copyright remains with the original authors |