The public money will fund projects exploring the real-world potential of “negative emissions” technologies (NETs), including soil carbon management, afforestation, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), enhanced weathering and direct capture of methane from the air.

NETs will “almost certainly be needed” to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change, one of the researchers tells Carbon Brief.

Yet there is huge uncertainty over whether it will be possible to deploy them quickly – and at scale – without causing knock-on environmental and social problems.

The new research programme is designed to investigate their potential, as well as the political, social and environmental issues surrounding their deployment.

It is coordinated by the UK’s government-funded National Environment Research Council (NERC). Carbon Brief has the details.

Paris goals

The Paris Agreement aims to keep warming “well below” 2C above pre-industrial temperatures, while striving to limit increases to 1.5C. It also aims for a “balance” between emissions sources and sinks in the second half of the century, equivalent to reaching global net-zero emissions.

Countries’ current pledges fall short of what will be needed, and the carbon budget for 1.5C will be used up within as little as four years. If cutting emissions is not enough, then the world will need greenhouse gas removal technology, also known as negative emissions.

A growing body of evidence suggests the world will need negative emissions to meet the Paris goals – and the UK will need them to meet its own, legally binding carbon targets.

Carbon Brief asked the lead scientist for each of the NERC-funded projects whether the UK or, more widely, the world would be able to meet their climate targets without greenhouse gas removal technologies.

Most of them agreed it was highly unlikely to be possible. See below for their detailed responses.

Prof Pete Smith, chair in plant and soil science at the University of Aberdeen, is leading one of the NERC research consortia. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Most models fail to reach a 2C target without greenhouse gas removal technologies, [so] I think they will almost certainly be needed to hit 2C – even more certain for the 1.5C target.”

A majority of pathways to 2C explored by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) include “very significant amounts” of negative emissions, Prof Smith adds, with up to 20bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) being removed per year.

This level of greenhouse gas removal would be the equivalent of sucking half of current annual global emissions out of the atmosphere.

Referring to the same IPCC pathways, Dr Naomi Vaughan, climate change lecturer at the University of East Anglia and another consortium lead, tells Carbon Brief that 101 of 116 scenarios for 2C rely on negative emissions. In the remaining 15, she notes, global emissions peak by 2010 – whereas in reality, emissions have risen since then.

The scenarios reflect a set of assumptions about the future, which may not turn out to be accurate. But if the world proceeds along those lines then “you either need a time machine or BECCS” to avoid 2C, Vaughan says.

New research

“To avoid dangerous climate change, we need to end the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere,” says Dr Phil Williamson of the University of East Anglia’s school of environmental sciences, who is the science coordinator of the new research programme.

“To end the increase, we need not only to reduce emissions, but to balance what is added by removals,” he says. “Yet we don’t yet know how those removals can be done at the scale required.”

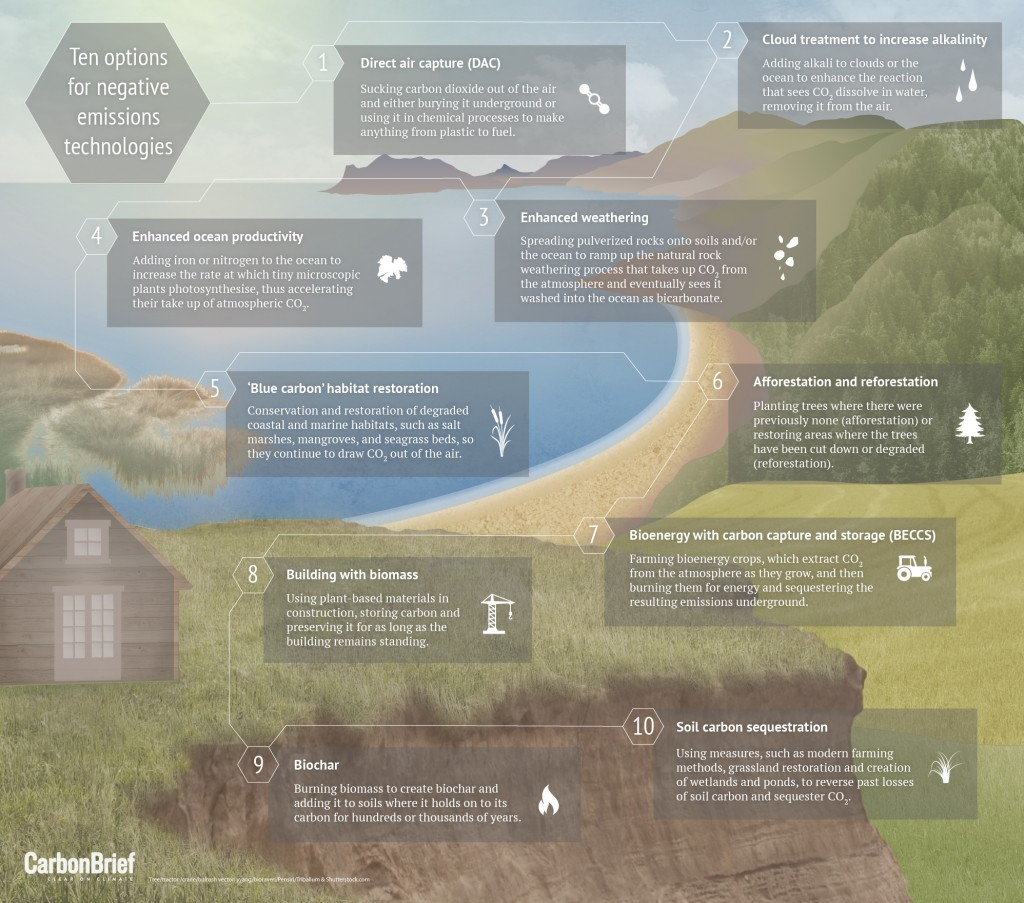

In a week-long series of articles published in 2016, Carbon Brief previously outlined the range of options available to achieve negative emissions, as well as the political, technical and environmental unknowns surrounding their use.

Infographic: Ten options for negative emissions. By Rosamund Pearce for Carbon Brief.

Two of the most common objections are that the technologies might fail, or that the prospect of being able to use them might allow society to put less emphasis on cutting emissions.

This is where the new UK research programme comes in. It will fund around 100 researchers at 40 UK universities and partner organisations to look into how feasible negative emissions technologies will be, and what might happen if we try to use them.

Dr Steve Smith, head of science at the UK’s Committee on Climate Change, tells Carbon Brief:

“This UK programme appears to be something of a world first in focussing on the ‘real world’ potential of greenhouse gas removal. Understanding this will be important for working out how to achieve the goal agreed in Paris of balancing sources and sinks of greenhouse gases.”

A €10m German research programme, launched in 2013, included some negative emissions projects as part of a wider range of topics related to climate engineering, sometimes described as geoengineering.

A US National Academy of Sciences committee will meet for the first time in May to discuss a research programme on carbon dioxide removal.

“

To avoid dangerous climate change, we need to end the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. To end the increase, we need not only to reduce emissions, but to balance what is added by removals. Yet we don’t yet know how those removals can be done at the scale required.

Phil Williamson, school of environmental sciences, University of East Anglia

The UK programme is divided into four large, interdisciplinary, multi-centre consortia, each receiving around £1.6m over 3-4 years. Another seven smaller research projects will each receive around £200,000 over the space of 18 months to three years.

It was developed after a scoping workshop, held last year. The work will complement a separate research programme funded by NERC and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), designed to explore pathways to 1.5C.

Stumbling blocks

The first consortium is split between the Imperial College, University College London and the universities of Oxford, Cambridge and East Anglia.

It will compare the technical potential of different greenhouse gas removal technologies (GGRs) with an analysis of their “political economy and social license to operate”. In other words, how likely it is that they will receive support from politicians and the public.

The project’s abstract says:

“Some portray GGR technologies as a panacea and virtually the only way of meeting aggressive climate targets…By contrast, sceptics have expressed concerns over moral hazard, the idea that pursuing these options may divert public and political attention…

Some critics have even invoked terms such ‘unicorns’, or ‘magical thinking’ to describe the view that many GGR technologies may be illusory.

“We will seek to understand these divergent framings and explicitly capture what could emerge as important social and political constraints on wide-scale deployment.

As with nuclear power, will many environmentalists come to view GGR technologies as an unacceptable option?”

Other questions include whether it would be better for the UK to import biomass, burn it for power and bury the resulting CO2, or if it would be preferable to pay for this to happen elsewhere.

Consortium lead Prof Niall Mac Dowell, head of the Imperial College clean fossil and bioenergy research group, tells Carbon Brief: “Whilst there are some important [technical] research questions that are still outstanding, the key stumbling block is, as always, policy.”

Moral hazard

One of the seven smaller research projects will focus explicitly on the question of moral hazard. Lancaster University’s Dr Nils Markusson is leading the work, asking whether pursuing greenhouse gas removal options could be a deterrent to emissions-cutting efforts.

Markusson tells Carbon Brief:

“The literature suggests that mitigation deterrence could happen in several ways. For example, there may be a so-called ‘moral hazard’ effect, whereby decision-makers feel less pressure to fund and implement mitigation, if they think that GGR technology will solve the problem…

In principle, it could also be true that GGRs complement or even reinforce mitigation efforts. We will study this, too, but this is a less worrying problem.”

Irreversible change

A second smaller project will look at the environmental implications of relying on greenhouse gas removal. Led by Prof Simon Tett, chair of earth system dynamics and modelling at Edinburgh University, it will ask if temporarily breaching 1.5C or 2C could have negative consequences, even if temperatures are later reduced using negative emissions.

These “overshoot” pathways are an increasingly common feature of modelled 1.5 or 2C scenarios, even though they may be less safe. Prof Tett and his colleague Dr Vivian Scott tell Carbon Brief:

“As a very simplified analogy: if you overcook a cake in the oven (overshoot the heating budget), then cool it down in the fridge afterwards (remove the excess heat) the cake you’re left with is not the same (impacts) as one that wasn’t overcooked to start with (no overshoot), despite the fact that the overall net heat received by each cake is the same.”

Life cycle assessment

A third smaller project, led by Dr Pietro Goglio, lecturer in life cycle assessment at the University of Cranfield, will attempt to compare different greenhouse gas removal options on a level playing field.

Goglio tells Carbon Brief it will do this by “improving current methods of assessment, which integrate environmental assessment, with economic models, with the social and political drivers”.

Soil carbon

The second large consortium, led by Aberdeen’s Prof Smith, is split between the universities of Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Newcastle and Cranfield, as well as Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC).

In the best tradition of scientific research acronyms, it is named: “Soils Research to deliver Greenhouse Gas REmovals and Abatement Technologies (Soils-R-GGREAT)”.

Prof Smith tells Carbon Brief the project aims to work out how much carbon could be removed globally by changing the way soils are managed, as well as how that potential varies by management practice and region.

It will be the “most comprehensive global assessment of the potential of our soils to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere,” Smith says. He adds:

“We have pulled together an exceptional team to tackle this challenge, with experts in soil science, computer modelling, socio-cultural-ecological impact assessment, economics, social science and life cycle assessments.”

Carbon accounting

Three smaller projects will explore related land-based options for greenhouse gas removals. One, led by Dr Joanna House, reader in environmental science and policy at the University of Bristol, will look at how to account for greenhouse gas removals in national emissions inventories.

House tells Carbon Brief: “Our work will will go towards ensuring transparency, accuracy and efficiency of land sector removals, raising ambition for even great efforts in the future.” She adds:

“There are many issues and uncertainties in the way land sector greenhouse gas fluxes are measured and reported. A lack of transparency could undermine efforts and fail to produce the required mitigation. My project addresses these issues.”

Farms with trees

Another smaller project, led by the University of Reading’s Dr Martin Lukac, will check the potential for greenhouse gas removal through agroforestry in the UK. Agroforestry combines existing farming land use with trees; for instance, widely-spaced rows planted across pasture or cropland.

Lukac tells Carbon Brief:

“Some of the grand schemes of using biomass growth to sequester CO2 rely on planting a lot of trees – but there is no space to plant large forests in the UK to provide biomass feedstock for power generation and CCS. We want to see (i) if farmers could be enticed to agroforestry and (ii) how much biomass they could actually generate.”

Capturing methane

Prof Euan Nisbet of Royal Holloway University of London will lead another smaller project on how to remove methane directly from the atmosphere. It hopes to find a way to deal with hard-to-eliminate methane emissions from widely distributed agricultural or industrial sources, such as livestock or gas pipelines.

Prof Nisbet tells Carbon Brief:

“We’re planning to use a mix of techniques…to investigate the problem of taking methane out of ambient air masses and to try to design very low cost ways of removing at least some of the methane coming from these intractable sources.”

BECCS

One of the most frequently cited options for negative emissions is biomass energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Carbon Brief explored the history of the concept last year. It is the focus of a third NERC-funded consortium, led by the University of East Anglia’s Dr Naomi Vaughan.

Given their prominence in current 2C pathways, Vaughan’s group hopes to take a holistic look at the feasibility of BECCS and afforestation. This will include a social-science analysis of whether it is socially or politically plausible to deploy BECCS at scale, Vaughan says, as well as the sorts of policies that might be needed to do so.

The project will work with Met Office climate scientists to explore any climate feedbacks that might be caused by forest expansion and large-scale bioenergy production, while engineers will help look across the BECCS supply chain to answer the question: “How can you make sure BECCS actually gives you the negative emissions that’s being assumed?”

Techniques including afforestation and soil carbon management already feature in many countries’ Paris climate pledges, Vaughan notes.

Enhanced weathering

Prof Gideon Henderson, head of the University of Oxford department of earth sciences, is leading the final large consortium. It will investigate the use of mining waste for greenhouse gas removal using so-called enhanced weathering.

Some metal ores, when exposed to air, combine with CO2 to form carbonate rocks. The consortium will assess how much suitable mining waste might be available, how quickly it can remove CO2 and ways to speed up the process. It will also check what will happen to the ocean if mining waste is added, as a way of accelerating negative emissions.

Industrial emissions

The final smaller research project, led by Cardiff University’s Dr Phil Renforth, will look at greenhouse gas removal in the iron and steel sectors. Fieldwork at current and former industrial sites at Consett in County Durham and Port Talbot in Wales, will check if iron and steel slag can be used to remove CO2 from the atmosphere.

Scientists’ views

Carbon Brief asked the lead scientist for each of the NERC-funded projects whether the UK or, more widely, the world would be able to meet their climate targets without greenhouse gas removal technologies. Here is what they said:

Prof Pete Smith, chair in plant and soil science at the University of Aberdeen:

“A majority of IPCC scenarios show that often very significant amounts (20 Gt CO2e/yr) of Greenhouse Gas Removal technologies (GGRs) are required to reach a 2°C target by 2100. Given that most models fail to reach a 2°C target without GGRs, I think they will almost certainly be needed to hit 2°C – even more certain for the 1.5°C target.”

Dr Naomi Vaughan, climate change lecturer at the University of East Anglia:

“I think that it’s highly unlikely to meet international goals without some form of negative emissions technology.” In the IPCC scenarios: “You either need a time machine or BECCS,” to avoid 2C.

Dr Niall Mac Dowell, head of the Imperial College clean fossil and bioenergy research group:

“Achieving our climate goals is possible via a combination of BECCS and DAC [direct air capture] – from a technical perspective. However, there is no way that this can happen unless these technologies are deployed at scale as soon as possible.

“Whilst there are some important research questions that are still outstanding, the key stumbling block is, as always, policy. Tackling our climate change commitments and meeting the Paris goals requires urgent policy/political action in order to create an environment conducive to deploying BECCS and DAC.

Importantly, I’m not sure we get GGR without first getting CCS [carbon capture and sequestration technology], so we really need to see more action on CCS in the near/medium term so we can get on to GGR in the medium/long term.”

Dr Jo House, reader in environmental science and policy at the University of Bristol:

“The Paris Agreement calls for net-zero emissions. While it may be possible to massively decarbonise the energy sector with transformational change, it is not possible to stop greenhouse gas emissions from the land sector and still feed the world, thus we will need ‘negative’ emissions.

“The land sector causes 25 per cent of net greenhouse gas emissions and 10 per cent of CO2 emissions, yet the land is naturally also a sink for around a thirds of anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

“The land sector can provide further carbon uptake through soil sequestration, afforestation and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage. Soil sequestration and afforestation can take up carbon dioxide immediately, it does not rely on technological development.

“Reducing land-sector emissions and promoting land-sector carbon sequestration could make a big difference in many countries. Globally, the land sector is critical in meeting the Paris goals, and in fact a quarter of pledged mitigation under Paris comes from the land sector.

“In the UK, the land sector is also important for meeting UK goals, but here decarbonising energy is even more critical. However, there are many issues and uncertainties in the way land-sector greenhouse gas fluxes are measured and reported. A lack of transparency could undermine efforts and fail to produce the required mitigation. My project addresses these issues.”

Dr Phil Renforth, lecturer in earth and ocean sciences at the University of Cardiff:

“Even if it were technically possible to reach the carbon budgets set out in the Paris accord without removal of CO2 from the atmosphere, which is looking increasingly unlikely, it may still be prudent to research and develop these proposals as a way of cutting the cost of hard to mitigate sectors.

“Essentially, this would chop the long tail off the marginal abatement cost curve. The importance of these technologies could have considerable impact on the economics of completely decarbonising our economy, and provide an insurance should conventional mitigation not be rolled out fast enough and we surpass a dangerous concentration of atmospheric CO2.”

Dr Martin Lukac, associate professor of agriculture, forestry and development at the University of Reading:

“Attainability of keeping below 2C warming without geoengineering (for that’s what these techniques essentially are): snowflake in hell springs to mind, unfortunately.

“The NASA Gistemp [global average surface temperature] anomaly for 2015 was more than +1C (2016 will be way higher than that but with a strong El Niño push so not very indicative, perhaps). We ‘achieved’ the +1C with a gradual rise of greenhouse gas emissions from near zero to about 10 billion tonnes of carbon per year.

“Now, one could argue that the emissions to increase global mean temperature by a further +1C have already been committed, plus we start chipping away the second half of our 2C allowance at the emission rate of 10 GtC, which we hope to decrease, but progress in unlikely to be fast enough even if everyone fulfills their Paris promises. And, as we all know, certain leaders of the free world have already indicated that they are not interested.”

Euan Nisbet, professor of earth sciences at Royal Holloway University of London:

“Methane is a hot topic at the moment. It’s rising fast and the causes of the rise seem to be meteorological, not directly anthropogenic. There’s a lot of discussion about why the rise is taking place – more emissions, or changing sinks? – but, either way, this may be a climate change feedback.

“This is important for the Paris Agreement, especially as methane’s global warming impact has recently been significantly reevaluated upwards. The progress we may make in cutting CO2 emissions may be negated by the unexpected methane rise.

“The best way to cut methane is to stop emissions. Obviously, the starting point is to reduce gas leaks from the natural gas industry and to cover landfills, etc. But there are also wide disseminated emissions from cattle (including winter cattle barns and also feedlots), active cells in landfills, gas compressors turning on and off, etc, that are much more intractable.

“Our new project is designed to tackle these ‘intractable’ methane emissions, where the methane is mixed into ambient air, in some tens of parts per million. Can we hope to do anything about these? We’re planning to use a mix of techniques, including catalytic removal systems based on our lab zero air systems, and also soil methanotrophy, to investigate the problem of taking methane out of ambient air masses, and to try to design very low cost ways of removing at least some of the methane coming from these intractable sources.”

Prof Simon Tett, chair of earth system dynamics and modelling at the University of Edinburgh, and Dr Vivian Scott, University of Edinburgh research associate in CO2 storage:

“With respect to achieving the Paris goals, short of extraordinary and unprecedented societal, economic and technological transformation, these appear to be extremely challenging without substantial (Gigatonnes CO2e per year) greenhouse gas removal.

“However, greenhouse gas removal at these scales may be as challenging and [our project] will test if there will be some climate change damages from this delayed GGR approach.”

“With respect to the UK, it to some extent depends on the system boundaries. The current Climate Change Act target of 80% by 2050 suggests that the UK can still be emitting GHGs in the 2050s and doesn’t account for all the embedded emissions in imports.

“Similar system boundary reflections might apply to UK greenhouse gas removal if it was used to contribute towards reaching targets. For example, given its huge geological CO2 storage resources the UK could undertake BECCS, but would be unlikely to be able to source the biomass feedstock for this from within the UK without wholesale transformation of the UK’s land-use.”

Dr Pietro Goglio, lecturer in lifecycle assessment at the University of Cranfield:

“The science basis behind the Paris Agreement shows clearly that without further exploitation of greenhouse gas removal technologies, the targets set may not be met.”

Dr Nils Markusson, lecturer at Lancaster University environment centre:

“I doubt [the targets can be met without negative emissions], but I’m also not sure that GGR (greenhouse gas removal) technologies are the solution for that problem.

“It is common to presume that we can just add the benefits of GGRs to the benefits of mitigation, to make up for the slow progress with mitigation (and the lingering effects of greenhouse gases we have already emitted). But, there is also an ongoing debate about whether using, or even just talking about using, GGRs can further undermine mitigation efforts (for example, replacing coal-fired power stations with windmills).

“In our research project, we will study what we call interaction effects between GGRs and mitigation to try to assess the risk of GGRs deterring mitigation.

“The literature suggests that mitigation deterrence could happen in several ways. For example, there may be a so-called ‘moral hazard’ effect, whereby decision makers feel less pressure to fund and implement mitigation, if they think that GGR technology will solve the problem. If there is a substantial risk of such deterrence then the hope we place in GGRs needs to be tempered accordingly.

“In principle, it could also be true that GGRs complement or even reinforce mitigation efforts. We will study this too, but this is a less worrying problem in terms of dealing with the problem of anthropogenic climate change.”