Despite another banner year for renewables growth in China, the country’s grid is still struggling to bring clean electricity to consumers. The problem is so serious in China’s north and west that turbines were forced to sit idle for much of 2016.

In response, China’s policymakers are now turning to energy storage to boost the grid’s ability to accommodate wind and solar power.

But significantly increasing the share of renewables will require big changes in how China operates the grid, raising questions about how much of a role energy storage will play in ensuring that renewable energy is not wasted through curtailment.

China’s energy storage push

Energy storage technologies – which include batteries, thermal storage, pumped hydro, and more – can help integrate wind and solar on to the grid by storing energy when power demand is low, and discharging power when demand is high.

Energy storage adds flexibility to the grid, allowing renewables to generate power when they would otherwise be curtailed.

Recognising this value, China’s policymakers are planning a rapid expansion of the country’s energy storage capacity. To start, policymakers are calling for new construction of pumped hydro storage facilities, which store energy by pumping water uphill into reservoirs where it can later flow down again through turbines to generate electricity.

The 13th Five-Year Hydropower Plan calls for an increase in pumped hydro storage from 23 gigawatts to 40 gigawatts by 2020 – about double the existing pumped hydro capacity of the United States.

“

Institutions to support transparency, monitoring, and enforcement are somewhat lacking in capacity, and state-owned enterprises currently dominate the industry.

Wang Xuan and Max Dupuy, power sector reform experts, Regulatory Assistance Project

The government is also promoting emerging energy storage technologies. In March 2016, the central government released a fifteen-year Energy Technology Innovation Action Plan calling for further research into advanced energy storage to support renewables integration, microgrid development, and electric vehicles.

One such demonstration project is already underway. In April 2016, the National Energy Administration approved the construction of a giant energy storage project in the northeast city of Dalian, where Chinese battery manufacturer Dalian Rongke is now building a 200-megawatt vanadium redox flow battery facility – a system so large that it will nearly triple China’s present grid-connected battery capacity when it is completed in 2018.

Government planners hope that the system will help address renewable energy curtailment in the region, in addition to providing back-up power and other services.

Private investment

The country is also piloting new mechanisms to encourage private investment in energy storage. Until recently, battery storage companies have had few avenues for commercial success. Nearly all deployments have been small-scale demonstration projects or installations in places where electricity is particularly expensive, such as remote areas and island grids.

But in June 2016, the National Energy Administration (NEA) unveiled an energy storage compensation scheme in northern China, where wind and solar curtailment is most severe. The programme pays energy storage providers for storing energy at night for use during the day.

The mechanism works by taking advantage of an existing paid service normally provided by coal plants, called peak regulation. In northern China, coal generation is used to provide electricity during the day and to provide essential heating through district heating networks.

Unfortunately, coal plants cannot be turned on or off easily and so must remain operating at night even when they’re unneeded. Although it’s less efficient, wind generators are asked to curtail power instead.

Currently, coal plants are compensated for having to ramp down power beyond a certain level. But instead of paying coal plants to not produce electricity, the new compensation mechanism pays energy storage to absorb excess power.

This means fewer coal plants in operation, more efficient coal-burning in those coal plants that remain operational, less wind curtailment, and a financial saving for the grid.

Because China’s power sector is in a transition state, it is still unclear how compensation for storage will change in the coming years. Nonetheless, this mechanism is a strong indicator that policymakers are ready to put advanced energy storage to work.

Adapting the grid

Energy storage can do a lot to help integrate renewables on to the grid. But at low levels of wind and solar penetration, it’s not strictly necessary to prevent curtailment. Instead, optimising grid operations is the key to integrating solar and wind power.

A US National Renewable Energy Laboratory study concluded that over 20 per cent of electricity in the US could come from wind generation without significant curtailment or the need for energy storage.

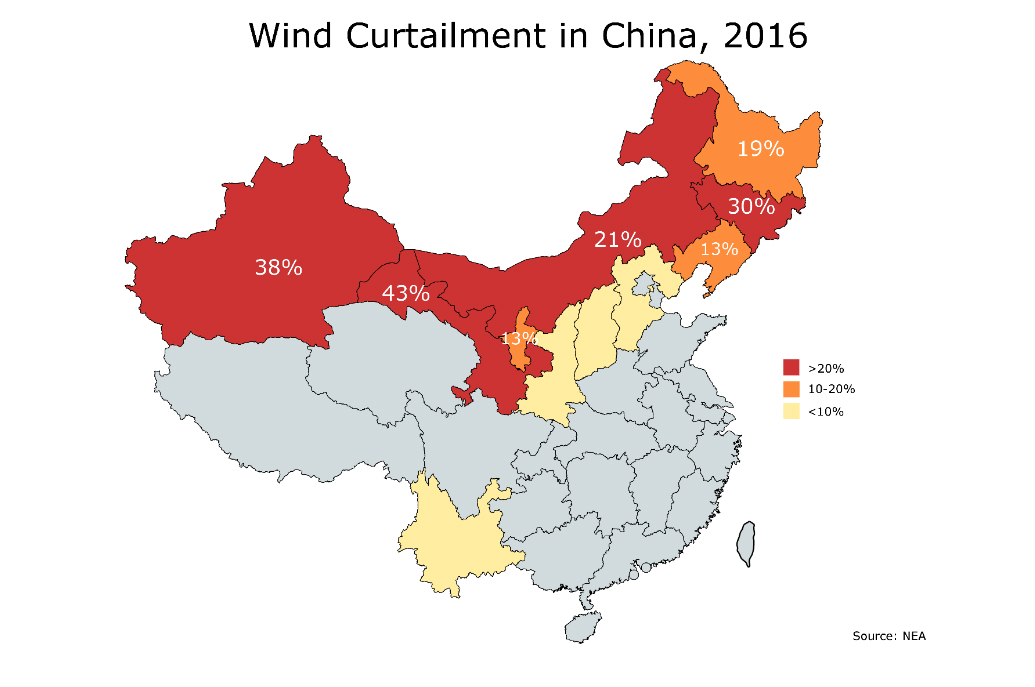

By comparison, wind accounted for only 4 per cent of China’s electricity production in 2016, yet provinces with high deployments of wind generation like Jilin, Xinjiang and Gansu respectively wasted 30 per cent, 38 per cent and 43 per cent of their potential wind output last year, according to the NEA.

Much of China’s curtailment challenge arises from institutional problems in its power sector planning and operations. Many of the practices that govern China’s grid today still prioritise coal as part of a planned economy rather than adapting to the needs of a diversified power sector.

This approach has tended to favour coal-fired generation at the expense of renewable generators. It has led to a mismatch between wind generation and transmission planning, which has left western wind farms sitting idle while waiting for transmission lines to be built to carry power to China’s demand centres in the east.

China’s approach to electricity dispatch has also Balkanised the country’s grids into provincial networks with inflexible means of balancing power supply and demand across the country.

At the moment, provincial governments are incentivised to dispatch power locally to support their tax base and oppose importing renewable energy from wind-rich provinces to protect the financial health of local fossil fuel generators.

Addressing these institutional barriers to clean energy integration is crucial to meeting the country’s air quality and carbon emissions targets. Yet policymakers have found it difficult to implement the reforms needed to reduce curtailment.

Although China introduced a new round of power sector reforms in 2015, some changes that would increase renewable energy utilisation – such as optimising power dispatch based on marginal cost – have been slow-coming.

Energy storage may be an attractive engineering solution to curtailment, especially as the prices of new energy storage technologies continue to fall, but given the political challenges it will remain one tool among many to help policymakers bring more renewables on to the grid.

Market barriers persist

But to make an impact, energy storage developers need the right investment signals and market reforms.

Despite the new storage compensation mechanisms in northern China, industry observers argue that China’s lack of electricity spot markets is hindering the widespread deployment of storage

“One important use of spot markets is to sell electricity at its true price as it changes with time,” writes Tina Zhang, secretary-general of the China Energy Research Society’s Energy Storage Committee.

These markets appear to be on the way: the 13th Five-Year Power Plan calls for pilot spot markets by 2018 and nationwide implementation by 2020.

But some observers contend that designing an effective spot market will be difficult. “China will face particular challenges in establishing competitive bidding in spot markets,” according to Wang Xuan and Max Dupuy, power sector reform experts at the Regulatory Assistance Project, a global NGO that advises governments on clean energy policy.

“Institutions to support transparency, monitoring, and enforcement are somewhat lacking in capacity, and state-owned enterprises currently dominate the industry.”

This suggests that energy storage providers will have to wait before their products can make an impact on wind and solar curtailment in China.

Beyond addressing curtailment, energy storage may end up serving other roles in China’s future grid. Energy storage can help reduce the costs of upgrading transmission and distribution networks, provide back-up power and address small imbalances in supply and demand. In short, these technologies can create a more reliable, cost-effective, and clean grid.

But until the right policies and regulations are put into action, China’s renewables-friendly future remains remote.