Women who aim for high political office often face plenty of challenges along the way. As a result, “they have an ability to resist and lead which is undoubtedly stronger than that of most men with a typical career path,” says Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo.

That hardiness is coming in handy as many of the world’s cities - a growing number of them led by women - move to take the lead in adopting clean energy, adapting to climate threats and otherwise battling climate change.

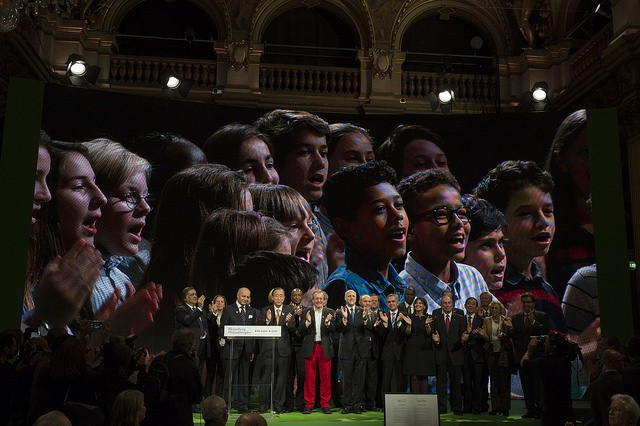

Women “have the courage to bring about those changes,” said Hidalgo, Paris’ first woman mayor and the first female leader of a global network of more than 80 cities leading on climate action.

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo

In two years, the number of women in charge of large cities that are taking the lead on climate change has risen from four to 16, according to C40 Cities, which is organising a conference for women leaders in New York this month.

Hidalgo, who took office in 2014, has set ambitious goals for the French capital - among them cleaning up Paris’ noxious air and making the River Seine swimmable again by 2024.

Making them a reality will take significant changes in how the city works - and standing up to the resistance to those changes, she said.

“

The key to fighting climate change is in the hands of mayors - not those of the president.

Anne Hidalgo, mayor, Paris

Cars banned from riverbank

For instance, her plan to reduce the use of cars in the city - as part of a wider crackdown against air pollution - has led to the flagship closure of the highway along the right bank of the Seine,a move that has infuriated a vocal minority of drivers.

The banks of the Seine from the Bir Hakeim bridge to Ile Saint Louis were made a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1991. The right bank highway runs past some of the capital’s main landmarks - the Ile de la Cite, Notre Dame and Paris city hall.

Hidalgo announced the road’s closure in 2016, as part of a war against polluting cars that is seeing large swathes of the city repurposed for cycling, walking and “breathing”, she said.

In 2013, Paris, under Hidalgo’s predecessor, traffic was banned from the left bank highway between the Musee d’Orsay and the Eiffel Tower. The area is now a popular park with outdoor cafes and sports facilities.

Pollution from vehicles in the City of Light often builds up into a greyish haze over the city and is becoming an increasing concern to local health authorities.

Several opinion polls showed last year that a majority of Parisians supported the closure of the river bank, Hidalgo said. Amid the fury among drivers over the closure, these were “people who weren’t given a voice,” Hidalgo told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in a phone interview.

She cited “women, mothers, children, people who suffer from breathing problems or chronic diseases” as unheard supporters of her environmental policy.

Armed with colour-coded stickers to mark older and more polluting vehicles, local authorities started restricting car use in the capital earlier this year, particularly diesel cars which they aim to ban completely by the end of Hidalgo’s six-year mandate, in 2020.

Paris last month also launched its first driverless electric shuttle bus service, aiming to curb the congestion and pollution that many Parisians blame for coughing, eye irritation and runny noses.

In an even more ambitious - though probably less likely - plan, Hidalgo wants to clean up the Seine to render it swimmable in time for the 2024 Olympics, for which Paris has put a bid.

According to the mayor, the fight against pollution is merely “one of the first signs of respect of a city for its inhabitants.”

Leading by example

When it comes to cutting pollution, Hidalgo says she is trying to lead by example. Although she mostly uses an electric car for work-related travel, she says she no longer owns a car in her personal life.

Instead, she uses “Autolib,” the capital’s electric car sharing scheme rolled out in 2011.

The mayor said she also always brings her own bags when she goes to the supermarket - where she buys organic food - in order to limit waste in a country that banned single-use plastic bags last year.

Globally, despite environmental pushbacks and uncertainty because of US President Donald Trump’s decision to step back from action on climate change, the future looks bright, she said.

“I am mostly positive,” she said, adding that “cities and businesses have understood that the environmental revolution could open up new markets and opportunities”.

Trump campaigned on promises to reverse the climate-change initiatives of his predecessor and withdraw from a Paris climate deal backed by nearly 200 countries in late 2015 to curb global warming by cutting greenhouse gases.

But Hidalgo is not overly concerned.

“I hope that the United States will not pull out of this historical agreement,” she said.

“But should they be tempted to, the key to fighting climate change is in the hands of mayors - not those of the president.”