|

| Reviews and Templates for Expression We |

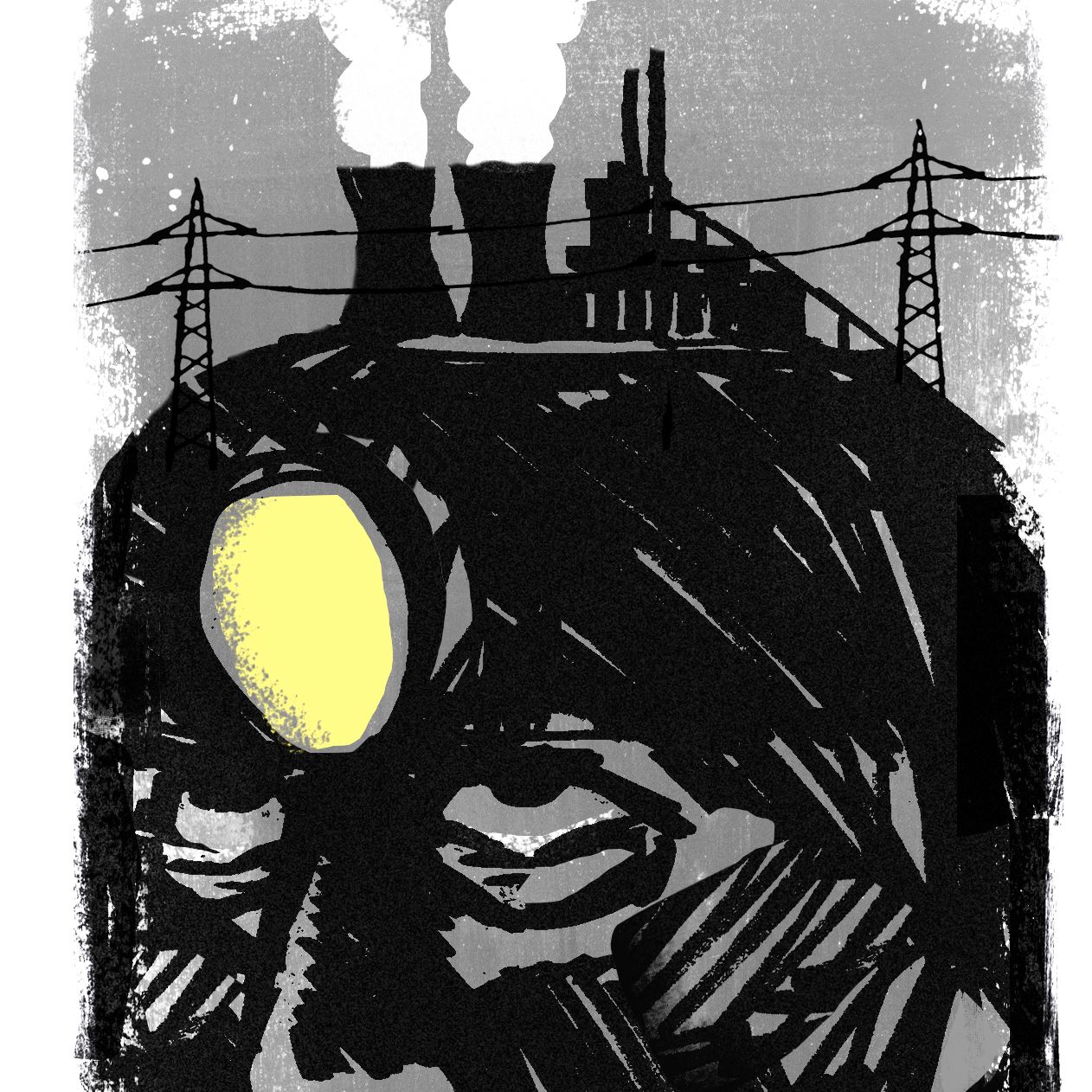

Coal will not recover

Falling prices for other fuels, not regulation, is what’s killing coal

Daniel Marsula/Post-Gazette

Daniel Marsula/Post-GazetteCoal production in the United States has declined enormously in recent years due to the simple reason that the coal-fired power industry is producing less of the country’s electricity than ever.

As recently as 10 years ago, coal-fired power plants provided half of America’s power needs. Today that number is closer to 30 percent — and falling. Coal is not likely to fade entirely from the scene any time soon, but informed analysts see its share of the U.S. energy mix dropping to less than 20 percent in the not distant future.

This is largely a market phenomenon driven by cheap natural gas and low-cost renewable wind and solar, which, because they are so inexpensive, have become go-to fuels for power generation. Coal does not have a regulation problem, as the industry claims. Instead, it has a growing market problem, as other technologies are increasingly able to produce electricity at lower cost. And that trend is unlikely to end.

True, there has been a recent uptick in coal prices. But there is no evidence that this represents a lasting long-term trend. The fundamentals behind the coal industry’s decline haven’t changed. Natural gas is still cheap. Renewables — wind in particular and now the fast-emerging solar industry — are taking business away from coal-fired generation.

Our organization just published a research paper that details these trends in Texas, one of the single biggest electricity markets in the country, where a growing number of major coal-fired power plants are at risk of closure because they can no longer compete.

Our research shows that many coal-fired power plants in Texas no longer act as “baseload plants,” and are instead limited to operations during peak-load periods. Although coal-fired plants generated 39 percent of the electricity on the Electric Reliability Council of Texas grid in Texas in early 2015, by May 2016 they provided only 24.8 percent.

Markets aside, public health and environmental regulations, including the Environmental Protection Agency’s regional haze rule, are forcing coal-fired power plant owners to decide whether to make expensive investments in their aging coal fleets. Our analysis suggests that such investments wouldn’t make much sense.

Indeed, a perfect storm of market, technological and regulatory developments are undermining the financial viability of many coal-fired generators across the country. Cheap natural gas and low energy prices in general are likely to persist. Wind-driven electricity will take a larger chunk out of the coal-fired industry, as will solar. Peak demand has been relatively flat, in part because of gains in energy efficiency, and that boils down to more competition for the same amount of the pie.

Solar and wind installation costs have declined dramatically in recent years. For example, wind prices have fallen to less than $30 per megawatt-hour from more than $60 in 2009. Because they have no fuel costs — the sun and wind are free — grid operators now transmit power from utility-scale solar and wind facilities ahead of coal-fired power. Solar generation acts to keep energy market prices low during periods of peak demand. Wind generation puts pressure on market prices in both peak and off-peak hours. The collective effect of solar and wind is making coal-fired electricity less and less financially viable.

Data snapshots drive home the growing impact of renewables. Wind provided 32 percent of the electricity produced from this past October through April in the northern Midwest. Just over 48 percent of the load on the ERCOT grid came from wind on March 23 — a remarkable single-day milestone that inevitably will be eclipsed.

The decline of coal is long term and irreversible, and it is happening now. Data published this month by S&P Global Market Intelligence shows a 26 percent decline in U.S. coal production in the first six months of this year. A short-term jump in coal price will not spell an industry comeback from the industry’s long-term decline.

As coal companies emerge from bankruptcy, they face a tough row to hoe and, judging from market and policy trends, it will not get any easier.

|

|

|

|

Copyright remains with the original authors |