|

| Reviews and Templates for Expression We |

Why cows are the new palm oil for retail supply chains

This story originally appeared at Ecosystem Marketplace.

Many retailers are at risk of stocking products sourced from cattle raised on recently deforested tropical forest lands. However, some retailers have relatively greater exposure to this problem — as well as greater power to address it.

Twenty-nine retailers selling cattle-derived products — ranging from steaks and burgers to shoes and handbags — are listed as "powerbrokers" on the Forest 500, the global rainforest ratings agency, run by the Global Canopy Program that identifies and ranks the most influential companies, investors and governments in the race towards a deforestation-free global economy.

Based on the Forest 500 identification process, these 29 companies constitute the most important retailers in the world when it comes to addressing tropical deforestation in global cattle supply chains.

And there is much to be done.

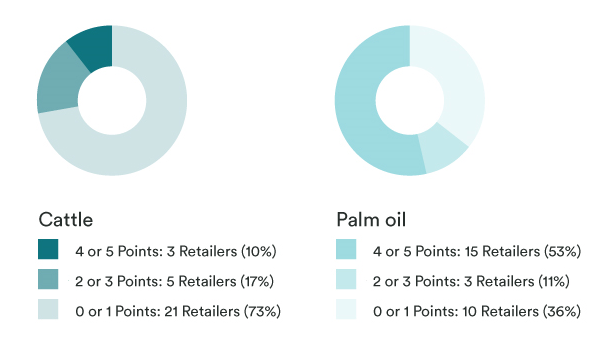

Based on last year’s annual Forest 500 assessment, only three (10 percent) of the 29 retailers received four out of the maximum five points available for policies related to cattle and deforestation. This reflects reasonable efforts by the three companies — Marks and Spencer, Burger King and Walmart — but also shows that strong policy leadership in this supply chain has yet to fully emerge.

Meanwhile, five companies had scores of only two or three, and 21 companies received no points at all, indicating that most of the 29 retailers are lagging behind significantly in terms of policies for cattle products.

There is a striking difference between these results for cattle and the scores of the same 29 companies for their policies on palm oil, for which 15 companies (over 50 percent) achieved four or even five points. This contrast is illustrated in a new retailer scorecard published on the ZeroDeforestationCattle.org website using data from the Forest 500.

This figure, from the new scorecard, illustrates that only 10 percent of retailers achieved a score of four or five for cattle, but over 50 percent of the same retailers scored four or five points for palm oil.

The results show that most of the 29 retailers are far less active in avoiding deforestation in their cattle supply chains than in their palm oil supply chains. This suggests a lack of understanding of and/or attention to the origins of the cattle products they sell, and the impacts their sourcing could have on forest cover, biodiversity and local communities in the tropics.

Of particular concern are the seven countries highlighted among the Forest 500 as being most vulnerable to deforestation driven by cattle production: Argentina; Brazil; Bolivia; Colombia; Mexico; Peru; and Venezuela.

The good news is that, for those companies that score badly for cattle but well for palm oil, transferring the zero deforestation concept from one commodity to the other should not require unprecedented leaps in thinking.

Of course, there are important differences between these supply chains. For example, while palm oil plantations have fixed locations, cattle are often moved between ranches as they are brought from the initial calving phase to final fattening.

These changes in ownership from ranch to ranch create challenges in terms of supply chain traceability. This adds a layer of complexity to the task of tracing beef and leather back to their origins, and understanding at which points in the production process deforestation is occurring.

However, this level of traceability must be accomplished if retailers are to be able to give assurance that the beef and leather products on their shelves are not contributing to tropical deforestation.

Retailers can drive progress internally and among their suppliers by developing a time-bound zero deforestation commitment for cattle products or by simply including cattle products in their existing deforestation policy.

Suppliers can be selected, and hence incentivized, on the basis of their own commitments and efforts towards zero deforestation, tracking and transparency. Retailers also can stimulate widespread improvement by ensuring that their deforestation (and sustainability) policies apply to all their own-brand products and operations globally.

Such policies would provide welcome and necessary synergies with existing measures in other parts of the supply chain, such as the Zero Deforestation Cattle Agreement, signed in 2009 by Brazil’s largest meatpackers, to not purchase cattle linked to deforestation or slave labor in the Brazilian Amazon.

Meanwhile, for companies performing poorly across the board, the Forest 500 assessment can provide a useful guide towards getting started on the path to deforestation-free supply chains.

The next assessment results will be announced at the end of 2016. Better scores in the cattle supply chain would be a significant cause for celebration.

|

|

|

|

Copyright remains with the original authors |