|

| Reviews and Templates for Expression We |

The Paris Climate Agreement – implications for New Zealand businesses

After lengthy and at times frustratingly slow and lengthy discussions, 196 countries successfully negotiated the legally binding Paris Climate Agreement that was presented on 12 December, 2015 at the 21st Conference of Parties of the UNFCCC. The intensive two week event has been well reported as having a successful outcome. Given the complexities of the negotiations and the major concerns of many developing countries concerning financing, equity and the goal for economic development, the French deserve full praise for their leadership and diplomacy to massage through the process to reach this stage.

The next step for the Paris Agreement is for parties to sign it, starting in New York on 22 April 2016 with ratification expected a year or more later. The Agreement will come into force when at least 55 parties, comprising at least 55% of global emissions, have ratified.

Given that Prime Minister John Key did not even mention “climate change” or the hugely significant Paris COP21 two week event in his recent ‘state-of-the nation’ speech, New Zealand is unlikely to be one of the early signatories.

John Key did attend the Leaders’ day at the start of COP 21 and also presented a communiqué from the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform (that New Zealand initiated) to Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC at a press conference. For this, as well as for the inadequacy of our Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC – see below), New Zealand received the first of the “Fossil of the Day” awards from the international youth delegations present. New Zealand has been independently reviewed to confirm we do have relatively low fossil fuel consumption subsidies, but if IEA accounting methods are used that include fossil fuel production subsidies (such as for oil and gas exploration), then that is a different story since fossil fuel subsidies have been calculated by WWF to be around NZ$ 46-80 million per year.

How challenging is the 2oC target?

Based on the latest IPCC science assessment, the Agreement recognised that the world needs to achieve a zero-carbon economy before the end of this century, but that the 188 INDCs submitted by parties before the COP are, together, inadequate as an early step along this transition pathway. The associated national greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation post-2020 targets, known as the INDCs, collectively would lead to an untenable 2.7 – 3oC future, rather than restrict global warming below the internationally agreed 2oC above pre-industrial levels.

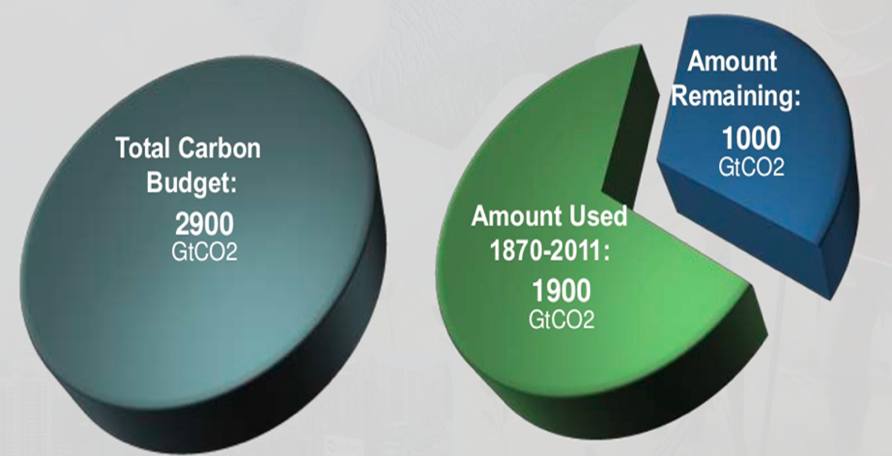

Even aiming to restrict the temperature rise to below 2oC is unacceptable to many, and a debate was won by small island states, including those in the South Pacific, to incorporate a more stringent 1.5oC target into the Agreement. However, this will be a huge challenge since IPCC analysis shows only a further total CO2 emission of around 500 Gt can be emitted to avoid exceeding 1.5oC. This carbon budget is likely to be rapidly used up in just the next decade under business-as-usual, especially given that many major developing countries such as China and India only intend to peak their GHG emissions by 2030 at the earliest as they continue to develop their economies. Achieving the lesser “below 2oC” target also involves a carbon budget; the projected rate of using up the remaining 1000 Gt CO2 (Fig. 1) under business-as-usual shows it is likely to be exceeded in around two decades.

Figure 1. Of the total budget of 2,900 Gt CO2 of anthropogenic CO2 emissions able to be emitted into the atmosphere in order to keep below the agreed 2oC temperature rise limit, around 1,900 Gt CO2 has already been released (IPCC, 2013).

Looking at the scale of the problem in another way, from 2000-2014 the global carbon intensity has been reduced by 1.3% per year on average, which sounds good but is grossly insufficient. This decarbonisation rate will have to be increased five-fold on average for every year until 2100 to avoid exceeding the 2oC level.

Before countries, including New Zealand, ratify the Agreement, there will be pressure imposed to review their mitigation “intentions” from 2020 to 2030, and to come up with far more ambitious Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). These are no longer “intentions” since they will need to be based largely on domestic mitigation actions. All countries are encouraged in the Agreement to declare, communicate and maintain their NDC targets, although they are not legally binding and without penalty if a party fails to meet its target, other than perhaps some loss of their international standing and credibility.

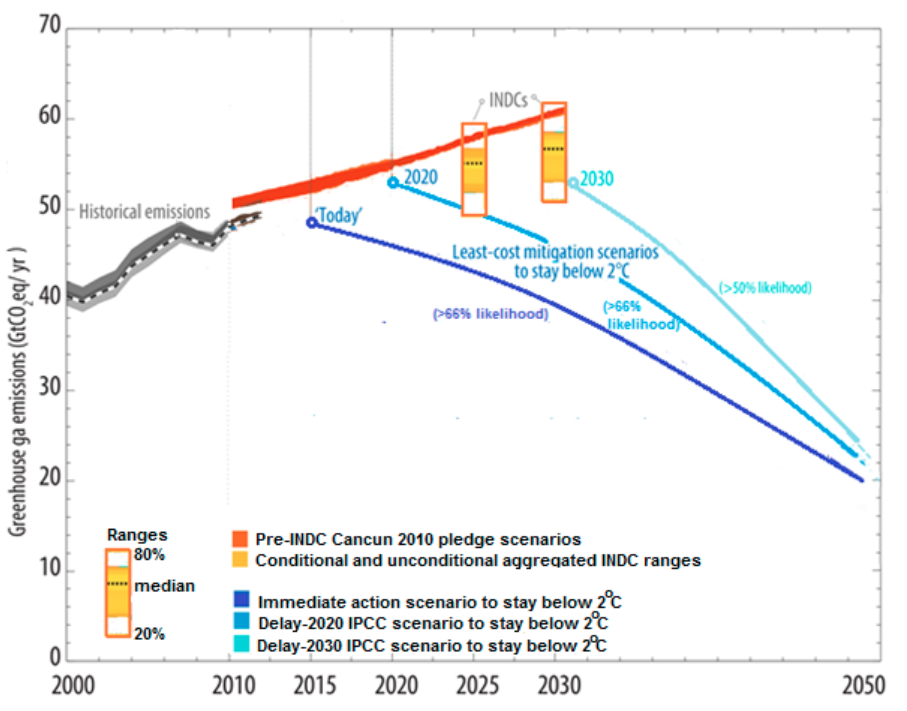

Many of the INDCs have conditions imposed, such as no action occurring without finance being forthcoming, or support for technology transfer, or in New Zealand’s case, acceptance of carbon markets and forest sinks. The range of INDC emission reductions by 2025 and 2030 as calculated by the UNFCCC will limit the on-going increase in annual global emissions to a level below that forecast based on pledges made in 2010 at COP 16 in Cancun, Mexico (Fig. 2). This analysis reinforced the message that less stringent GHG reduction pathways would be possible if peak emissions could occur sooner. The total emission reductions pledged in the INDCs give annual total GHG emissions increasing through to around 2025 to 2030 before peaking, after which a steeper and more rapid decline in GHG emissions will needed over the next few decades if we are to stay below the 2oC.

Figure 2. Based on the submitted INDCs, the projected global GHG emission reduction ranges in 2025 and 2030 (yellow boxes) have medians lower than the national pledges made at COP 16 in Cancun in 2010 (red line), but are still insufficient to keep temperature rise below 2oC (shown by the simplified blue pathways based on IPCC least-cost scenarios).

Civil society in Paris

A lot was also happening in Paris outside the negotiation rooms, with hundreds of meetings involving representatives from large and small businesses, cities, NGOs, finance companies, banks, international organisations and agencies etc. Many outlined their climate-based intentions and plans for investments in a low-carbon future, often supported by celebrities (e.g. Leonard diCaprio, Al Gore, Bill Gates, Richard Branson). Overall it reminded me of a 1980s Telethon: “Thank you very much for your kind donation”!

There is no doubt a huge momentum is underway for the world to transition away from fossil fuel combustion (the main contributor to GHG emissions). For example, a key statement made jointly by Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, and Michael Bloomberg, business magnate and former mayor of New York City, on the financial risks of climate change and the need to divest fossil fuel company investments, had many others sitting up and taking notice.

So what does the Paris Agreement imply for New Zealand?

The 32 page Agreement document consists of a “Draft decision” that sets conditions to its adoption, and 29 Articles of which Articles 2 and 4 are most relevant to mitigation opportunities for New Zealand.

The following statements, extracted directly from the Paris Climate Agreement, are compiled here to illustrate the direct impact that the Agreement could have on New Zealand’s policies and actions.

- This Agreement aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change. (Article 2, 1a)

- In order to achieve this long-term temperature goal, Parties aim to reach global peaking of GHG emissions as soon as possible and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of GHGs in the second half of this century, on the basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty. (Article 4, 1)

- Requests those Parties whose INDC contains a time frame up to 2030 to communicate or update by 2020 these contributions and to do so every five years. (Draft decision -/CP21, 24; Article 4, 9)

- Notes with concern that the estimated aggregate GHG emission levels in 2025 and 2030 resulting from the INDCs do not fall within least-cost 2 ˚C scenarios but rather lead to a projected level of 55 Gt in 2030, and also notes that much greater emission reduction efforts will be required than those associated with the INDCs in order to hold the increase in the global average temperature to below 2˚C above pre-industrial levels by reducing emissions to 40 Gt, or to 1.5˚C above pre-industrial levels by reducing to a level to be identified. (Draft decision -/CP21, 17).

- Each Party shall prepare, communicate and maintain successive Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that it intends to achieve. Parties shall pursue domestic mitigation measures, with the aim of achieving the objectives of such contributions. (Article 4, 2)

- Invites Parties to communicate by 2020, their mid-century, long-term, low GHG emission development strategies (in accordance with Article 4, 19) and requests the secretariat to publish on the UNFCCC website, the Parties’ low GHG emission development strategies as communicated. (Draft decision -/CP21, 36).

- All Parties should strive to formulate and communicate long-term low GHG emission development strategies, mindful of Article 2 taking into account their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances. (Article 4, 36)

- Decides to convene a facilitative dialogue among Parties in 2018 to take stock of the collective efforts of Parties in relation to progress towards the long-term goal (Article 4, 1) and to inform the preparation of NDCs (Article 4, 8).

- In communicating their NDCs, all Parties shall provide the information necessary for clarity, transparency and understanding in accordance with decision 1/CP.21 and any relevant decisions of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement. (Article 4, 8)

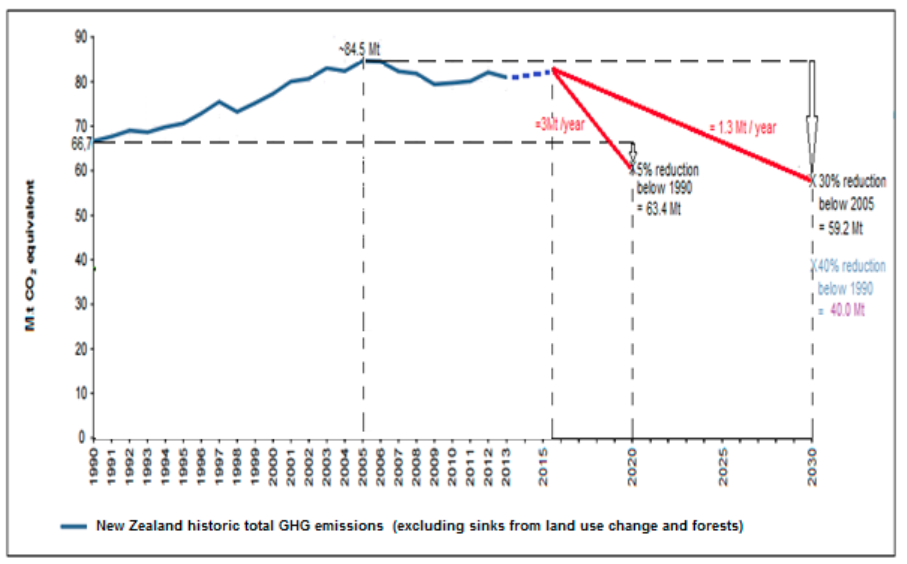

The New Zealand INDC target of 30% below 2005 national GHG emissions by 2030 (equivalent to 11.2% below 1990 levels) has been claimed by the government to be more ambitious than the previous target of 5% below 1990 levels by 2020, but since there is an additional decade involved, it only requires emission reductions of 1.3 Mt CO2-eq per year compared with 3 Mt/yr(Fig. 3).

Figure 3. New Zealand’s gross GHG emission levels from 1990 to 2015 and a comparison of the INDC 2030 target with the earlier 2020 target and with a more stringent 40% target.

(Note: Historic emissions taken from New Zealand’s Climate Change Target – discussion document, Ministry for the Environment, 2015.

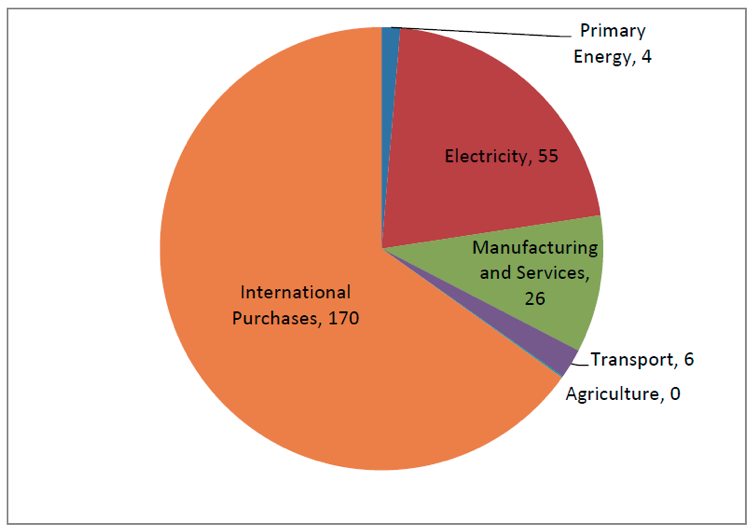

Over 15,000 submissions were received on the government’s INDC consultation process in May/June 2015. Almost 70% of the 10,900 submitters who mentioned the target sought at least 40% reduction below 1990 level by 2030 (Fig. 3). The government’s 30% INDC target that resulted was deemed “inadequate” by independent international assessors. In addition, the government is contemplating meeting most of this modest target by purchasing carbon credits off-shore (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Landcare’s modelling of New Zealand GHG mitigation potential by source of cumulative emissions over 2021-2030 period as linked with the INDC consultation process.

New Zealand’s INDC conditions that are linked to carbon trading, forest sinks and agricultural emissions remain undecided in the Paris Agreement.

- Carbon trading. In Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, international emission trading options are outlined:

“Countries can choose to pursue voluntary cooperation in the implementation of their NDCs to allow for higher ambition with any activities needing to be both transparent and accountable.”

The pricing of carbon comes under Decision 137 that: “recognizes the role of providing incentives for emission reduction activities such as domestic policies and carbon pricing”. A new sustainable development mechanism similar to the Clean Development Mechanism is to be established. The role for carbon markets is only briefly addressed in the Agreement under the term “internationally transferred mitigation outcomes”. So it appears carbon trading may be permissible although it will probably take several years of further deliberations before the rules of trading are agreed.

- Forest sinks. In relation to New Zealand’s interest in land use change and the growth of plantation forests to partly offset our CO2 emissions from fossil fuels, this was mentioned as “removal by sinks of GHGs” (Article 4, 1). Recognised in the Agreement is “the conservation and enhancement, as appropriate, of sinks and reservoirs” but this is also subject to a further detailed work programme over the next few years giving uncertainty over how much we might rely on forest sinks to offset our emissions in future.

- Agricultural emissions. For New Zealand’s agricultural sector that produces almost half of our total GHGs, the Agreement “recognises the fundamental priority of safeguarding food security and ending hunger, and the particular vulnerabilities of food production systems to the adverse impacts of climate change”. However, although over 100 countries have included mitigation of agricultural GHG emissions in their INDCs, no specific statement appears in the Agreement and again, an on-going work programme will be needed to consider the development of appropriate standard guidelines and methodologies.

Fossil fuel subsidy reform is not included in the Agreement but nevertheless is gaining international traction to remove both consumption and production subsidies. Interestingly, the G7 countries plus Australia invest around forty times more in fossil fuel subsidies (~USD 80 billion/yr) than their total contribution to the Green Climate Fund (GCF) that was established in 2009 with the aim for richer countries to help support poorer countries meet their mitigation and adaptation goals by committing US$ 100 billion per year by 2020. Before Paris, the GCF had funded its first projects but had only received commitments of around US$ 10 billion. Therefore, it is not surprising that “financing” was a key discussion point in the Paris negotiations, especially given that many of the INDCs are conditional on support from the GCF. Together they will require a cumulative investment from 2015 until 2030 of around USD13.5 trillion to support low carbon technologies, energy efficiency and adaptation actions.

Not explicitly covered in the Agreement, although discussed at length during the negotiations and various side-events, were emissions from international aviation and shipping. Steady progress has been made by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO)). Further work is being undertaken which, no doubt, will have impacts for New Zealand given our isolation, increasing tourism numbers, and high-volume exports.

What might happen next?

France, that holds the COP Presidency until the COP 22 in Morocco at the end of this year, is actively encouraging countries before they ratify to strengthen their NDCs that cover the period 2021-30. In this regard, the Royal Society of New Zealand has established a Climate Change Mitigation Panel to assess New Zealand’s GHG mitigation opportunities. The latest scientific knowledge on mitigation will be reviewed and opportunities identified for New Zealand to both reduce emissions whilst benefitting from the social and behavioural changes involved. The aim of the study is to:

- identify the potential for options available to reduce our GHG emissions across all sectors,

- identify the many associated co-benefits such as improved health, cost savings, and reduced traffic congestion, and

- communicate how businesses, towns, cities and households, can best reduce their carbon footprints.

In the Foreword to New Zealand’s 6th National Communication to the UNFCCC in 2013, Minister Groser stated “The emissions reduction opportunities available to other nations through conversion to renewables, mass public transport and energy efficiency in industry have already been done or have far less scope in New Zealand”. This is simply untrue on all three points. In order to “do our fair share” we should all be aiming to reduce our actual GHG emissions where ever feasible to do so. The world’s mitigation momentum is gaining speed and we don’t want to be left behind.

- “COP21” of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. http://newsroom.unfccc.int/

-

A full video recording of John Key’s speech is available here: http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/76303527/prime-minister-john-key-signals-early-start-for-auckland-city-rail-link

-

The range depends on what is included as a “subsidy”: http://www.wwf.org.nz/?10762/New-report-exposes-Government-hypocrisy-on-fossil-fuel-subsidies; http://www.wwf.org.nz/?13262/Government-needs-to-come-clean-on-its-own-fossil-fuel-subsidies

-

IPCC’s Climate Change 2014 – Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/syr/AR5_SYR_FINAL_SPM.pdf

- http://www.newsweek.com/financial-risks-climate-change-cop21-bloomberg-carney-paris-summit-403484?rx=us

-

New Zealand’s Addendum to the INDC (November 2015) shows the intentions for forests and land use. http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/New%20Zealand/1/NZ%20INDC%20Addendum%2025%2011%202015.pdf

- This phrase could also apply to carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS) from thermal power plants etc..

-

New Zealand has contributed NZ$ 3 million to the GCF, far less than its annual fossil fuel subsidies of around NZ$ 80 million. This contribution equates to around US$ 0.37 / capita compared with the UK contribution of US$ 18.47/capita and the US of USD 9.41/capita. However, New Zealand has also committed NZ$50 M/yr for 4 years to support South Pacific countries. Together that equates to around US$ 7.40/capita.

-

Energy and climate change, World Energy Outlook -special briefing for COP 21, International Energy Agency, OECD/IEA, Paris, 7 pages. http://www.iea.org/media/news/WEO_INDC_Paper_Final_WEB.PDF

-

New Zealand’s Sixth National Communication under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and Kyoto Protocol, Ministry for the Environment. http://img.scoop.co.nz/media/pdfs/1312/sixthnationalcommunication.pdf

|

|

|

|

Copyright 2011 Energy and Technical Services Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Energyts.com |