Global warming has not undergone a ‘pause’ or ‘hiatus’, according to US government research that undermines one of the key arguments used by sceptics to question climate science.

The new study reassessed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (Noaa) temperature record to account for changing methods of measuring the global surface temperature over the past century.

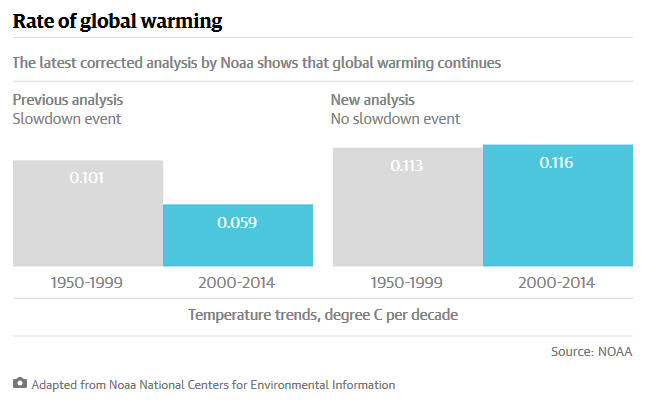

The adjustments to the data were slight, but removed a flattening of the graph this century that has led climate sceptics to claim the rise in global temperatures had stopped.

“There is no slowdown in warming, there is no hiatus,” said lead author Dr Tom Karl, who is the director of Noaa’s National Climatic Data Centre.

Dr Gavin Schmidt, a climatologist and the director of Nasa’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies said: “The fact that such small changes to the analysis make the difference between a hiatus or not merely underlines how fragile a concept it was in the first place.”

The results, published on Thursday in the journal Science, showed the rate of warming over the past 15 years (0.116C per decade) was almost exactly the same, in fact slightly higher, as the past five decades (0.113C per decade).

In 2013, the UN’s most comprehensive report on climate science made a tentative observation that the years since 1998 had seen a “much smaller increasing trend” than the preceding half century. The results highlighted the inadequacy of using the global mean surface temperature as the primary yardstick for climate change.

Karl said: “There’s been a lot of work done trying to understand the so-called hiatus and understand where is this missing heat.”

A series of studies have since identified a number of factors, including heat transferred into deep oceans and small volcanic eruptions, that affected the temperature at the surface of the Earth.

“Those studies are all quite valid and what they suggest is had those factors not occurred the warming rate would even be greater than what we report,” said Karl.

Dr Peter Stott, head of climate monitoring and attribution at the UK’s Met Office, said Noaa’s research was “robust” and mirrored an analysis the British team is conducting on its own surface temperature record.

“Their work is consistent with independent work that we’ve done. It’s within our uncertainties. Part of the robustness and reliability of these records is that there are different groups around the world doing this work,” he said.

But Stott argued that the term slowdown remained valid because the past 15 years might have been still hotter were it not for natural variations.

In the coming years the world is expected to move out of a period in which the gradient of warming has not slowed even though the temperature has been moderated. This means “we could have 10 or 15 years of very rapid rates of warming,” he said.

“Even though the observed estimate is increased, over and above that there is plenty of evidence that the rate of warming is still being depressed,” he said. “The caution is around saying that that is our underlying warming rate, because the climate models are predicting substantially higher rates than that.”

Noaa’s historical observations were thrown out by unaccounted-for differences between the measurements taken by ships using buckets and ships using thermometers in their engine in-takes, the increased use of ocean buoys and a large increase in the number of land-based monitoring stations.

“Science can only progress based on as much information as we have and what you see today is the most comprehensive assessment we can do based on all the information that’s been collected,” said Karl.

Schmidt called the new observations “state of the art” and said Nasa had been in discussions with Noaa about how to incorporate the findings into their own global temperature record.

Prof Michael Mann, whose analysis of the global temperature in the 1990s revolutionised the field, said the work underlined the conclusions of his own recent research.

“They’ve sort of just confirmed what we already knew, there is no true ‘pause’ or ‘hiatus’ in warming,” he said. “To the extent that the study further drives home the fact ... that global warming continues unabated as we continue to burn fossil fuels and warm the planet, it is nonetheless a useful contribution to the literature.”

Bob Ward, policy and communications director at London’s Grantham Research Institute, said the news that warming had been greater than previously thought should cause governments currently meeting in Bonn to act with renewed urgency and lay foundations for a strong agreement at the pivotal climate conference in Paris this December.

“The myth of the global warming pause has been heavily promoted by climate change sceptics seeking to undermine the case for strong and urgent cuts in greenhouse gas emissions,” said Ward.

Since scientists began to report a slower than expected rate of warming during the last decade, climate sceptics have latched on to the apparent dip in order to question the validity of climate models.

Last February, US Republican presidential candidate Ted Cruz told CNN: “The last 15 years, there has been no recorded warming. Contrary to all the theories that – that they are expounding, there should have been warming over the last 15 years. It hasn’t happened.”

Cruz’s rival for the Republican nomination, Jeb Bush, was using the pause to argue for inaction as early as 2009.

The Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF), the UK thinktank set up by Nigel Lawson to lobby against action on climate change and which hosts a flat-lining temperature graph on the masthead of its website, was dismissive of the study.

Dr David Whitehouse, an astrophysicist and science editor for the GWPF, said: “This is a highly speculative and slight paper that produces a statistically marginal result by cherry-picking time intervals.” He claimed the temperature graph was at odds with those of the Met Office and Nasa, despite both organisations saying the new study’s results were consistent with their data.