|

| Reviews and Templates for Expression We |

Is business our last great hope on climate change?

As I sit here writing this article, it has started raining again here in London. No surprises there, you might think. But even by soggy British standards, this summer has been extreme — the wettest for a century, meteorologists say. Communities in the north of England are under several feet of water, for the second time in less than three years.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, North America was until recently sweltering in a lengthy heat wave that has resulted in an estimated 82 deaths, while scientists report that the extent of polar ice melt this year has broken all records.

With mounting signs of a changing climate such as these, anyone trying to identify which issue should be at the heart of a company’s sustainability strategy -- and looking for clues as to where citizen and consumer expectations are headed -- might have expected public concern to be on the rise. But this does not appear to be the case.

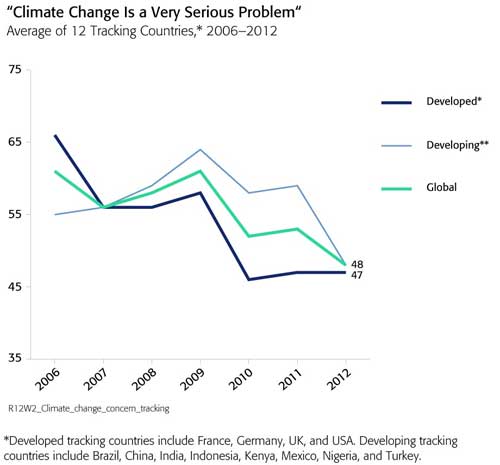

GlobeScan has been tracking public concern about climate change since the late 1990s. Polling representative samples of adults across the developed and developing world, we ask people to say how much of a problem they think climate change is, along with a range of other environmental issues.

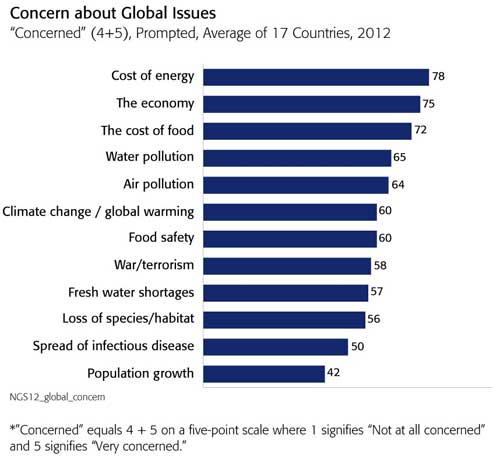

Fifteen years ago, climate change was a second-tier environmental concern in the public’s mind. People ranked it a long way behind immediately visible and tangible problems, such as water and air pollution, as well as other seemingly more concrete threats. For example, in 1998, 50 percent of people across our tracking countries felt climate change was a very serious issue, 60 percent felt the loss of biodiversity was very serious, and 64 percent felt the same way about resource depletion.

In the years that followed, however, climate change rose up the media and political agenda, and public concern started to rise. By the middle of the last decade, our tracking indicated that it had largely caught up with other environmental worries. Initiatives like Sir Nicholas Stern’s review here in the UK seemed to indicate that a political head of steam was building around the issue. The intergovernmental summit in Copenhagen was billed as the global community’s big chance to change course.

But the dynamic had already begun to shift again. The global economic boom came to a screeching halt in 2007 and public concern on climate reached a plateau. The Copenhagen summit, instead of being the catalyst for radical economic and political change that many had hoped, dissolved amid recriminations and accusations of bad faith, without a viable plan for containing the impacts of climate change.

From Copenhagen to China

The failure of Copenhagen also appeared to be the trigger for the public to start to disengage with the issue. When we first tracked public sentiment after the summit, we found that concern was down sharply, particularly in the developed economies. And while it reasserted itself to some degree last year, our latest figures show that the downward trajectory is now well established, largely because developing nations’ concerns -- which had seemed until then to be taking over the mantle of environmental leadership from the West -- are now elsewhere.

Most alarmingly, perhaps, the proportion of Chinese citizens rating climate change as a “very serious” problem over the past year has dropped from 55 percent to 40 percent, while our recent polling for National Geographic found the numbers of Chinese spontaneously mentioning the issue as the most important facing their country tumbled from 37 percent in 2010 to a mere 7 percent this year. With China opening a new coal-powered power plant every week or so, and a change of political leadership imminent, the consequences of climate change and carbon emissions falling off the Chinese political agenda could hardly be more acute.

What, then, is going on here -- and what can those with an interest in stopping climate change do about it?

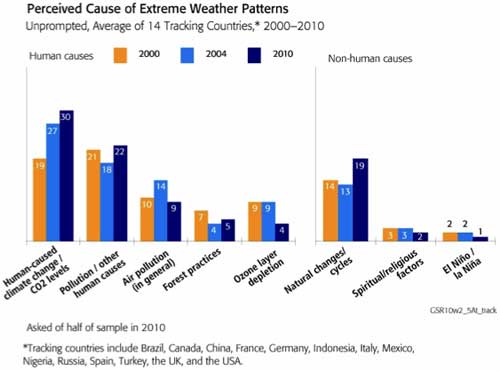

First, the politics. Climate change may be one of the most serious political problems the world has faced, but in many countries political polarization itself is turning into one of the major obstacles to progress. Our data demonstrates how, globally, attitudes have hardened on both sides of the argument, with the numbers attributing extreme weather events to human activity and those ascribing them to natural fluctuations both increasing over recent years.

The current U.S. election campaign illustrates this, with Mitt Romney only one example of a Republican leader who has felt the need to walk back his previous acknowledgment that human-caused climate change is a reality. The future looks bleak if right-of-center politicians around the world are unable to address the climate problem except to deny that it exists. If Romney loses in November, this is surely one issue where future nominees will need to challenge the new party orthodoxy.

It is telling also that concern among Americans about other environmental issues has been on the rise while climate concern has fallen from its 2007 peak. Climate change as an issue in the U.S. has become part of the culture wars, which doesn’t help anyone.

Second, the economy. It is clear that the state of the global economy seems to many citizens, particularly in the global North, like a much more immediate threat to their way of life. Our figures reveal that economic worries -- not just the complexities of this year’s Euro crisis, but the day-to-day realities of unemployment and rising prices -- remain top of mind. It would be odd if people did not at least subconsciously compare the swiftness with which the world’s political leaders were able to agree on coordinated action and massive funding to save the banking system from collapse with their apparent inability to achieve anywhere near the same level of consensus or investment in climate change mitigation, and come to the conclusion that the former posed the greater threat to civilisation.

Third, the public’s disinterest. It is clear that the climate change in the eyes of many ordinary people remains abstract, complex and depressing -- a dangerous combination. Society’s ambivalence towards scientists may be a factor here. Our regular tracking of public trust in institutions shows that scientists enjoy levels of public trust that far outstrip those of government, business, the media or even NGOs. Yet scientists are instinctively cautious in ascribing individual instances of extreme or unusual weather to the changing climate. Their nuanced language and reluctance to go out on a limb may be part of the reason why they are trusted by the public -- but they also mean that their message can be misconstrued or lost in translation by a media looking for certainties and clear narratives.

Amid all of this, the temptation for business must be to ignore the issue and hope that it goes away. That would be a mistake, and not only because the volatility of public sentiment suggests to us that climate concern may be on an upward curve again soon. Whether or not the public trusts companies -- and as we’ve previously noted in this column, many do not -- they at least have faith in their ability to make a difference.

And an issue that is so important, but where political leadership is so obviously lacking, must surely be a prime candidate for concerted action by the business community. They cannot do it alone, but visible evidence that companies recognize that the climate issue is not going away may be what is needed to place the issue back on the public agenda.

|

|

|

|

Copyright 2011 Energy and Technical Services Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Energyts.com |