Which of the following accounts for the largest share of the UK's carbon footprint? All our holiday flights, all the power used in our homes or … Russia?

Okay, so it's kind of a trick question, but according to a scientific paper published this week, we might reasonably conclude that the answer is Russia – though to understand why it's necessary to go back a couple of steps.

For the purposes of the Kyoto treaty, a nation's carbon footprint is considered to be a sum of all the greenhouse gas released within its borders. But as many people – myself included – have been pointing out for years, that approach ignores all the laptops, leggings, lampshades and other goods that rich countries import from China and elsewhere.

If we want any chance of a fair global climate deal, the now-familiar argument goes, we need to rethink the way we measure emissions to allocate some of the carbon pouring out of Chinese, Indian and Mexican factories and power plants to the countries importing good from those countries.

The new scientific paper, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, points out that this argument – though persuasive – tells only half of the story. If you want to understand how carbon footprints are affected by international trade flows, the paper argues, you need to consider trade not only in gadgets and garments but also in fossil fuels themselves. After all, though country X might import a television that was made in country Y, it's quite possible that country Y in turn imported some of the coal, oil or gas consumed by the television factory from country Z.

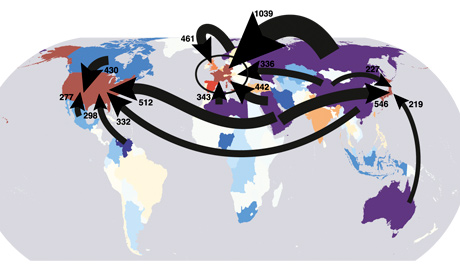

Of course, there's nothing revelatory in the idea that fossil fuels are traded between nations. We all know that, say, Saudi Arabia produces much of the world's oil. But what the academics behind the new data have done is a remarkable feat of number crunching: they've tracked the carbon flows of virtually the whole world, from the countries extracting the oil, gas and coal via the countries in which it's burned to the countries that ultimately consume the goods and services all that energy is used to create.

As a result, we can see how much of the coal mined in Australia is used to support lifestyles in the Europe; or what proportion of all the energy, goods and services consumed in Japan was ultimately created with oil from the Middle East.

All of which will appeal to climate data enthusiasts, but is the study actually important? I think it is – not so much because it has any obvious practical applications, but because the data helps reminds campaigners, consumers and policymakers alike that the climate-change problem is ultimately about fossil fuel coming out of the ground. That sounds an obvious thing to say but it's a point often forgotten in all the discussions about clean energy or national emissions cuts – both of which are necessary but not sufficient to meet the challenge of leaving most of the world's hydrocarbons in the ground.

To meet that challenge, we need a global climate deal. And to increase the chances of getting one, one of many things we need to do, I would argue, is to think more about the whole chain of responsibility and benefits related to fossil fuel use. It's easy to simplify the debate and say that the US or Europe are entirely responsible for the goods they import from China; but in truth China also benefit economically from that trade and – crucially – so do the powers that be in the countries that provide China with its oil imports.

Which takes us back to the question I posed at the beginning of this post. Russia, it turns out, provides about 6.8% of the fossil fuels burned in the UK. It also exports its fuels to other countries, which in turn export goods to us. All told, Russian fuels account for almost a tenth of our national carbon footprint – more than our domestic electricity use or our leisure flights.

Does that make Russia 10% responsible for the UK's footprint? No, of course not. But in the same way that most of us would allocate some of the responsibility for drug use to the producers and importers, or of gun crime to the small arms manufacturers, or of chemical pollution to the chemical companies, surely we need to start thinking of responsibility for fossil fuel use in a more nuanced way. It's global emissions that matter – and globally the economic benefits of fossil fuel use are widely spread around.