|

| Reviews and Templates for Expression We |

Getting Sick on Pesticides Big Ag Can't Live Without

Pesticides are engineered to kill living organisms in a number of ways, including destroying the nervous system of the insects they target. They can't be good for human health either.

Earlier this year, three separate studies published at the same time reached very similar, and very disturbing, conclusions: Children exposed to the organophosphate or "OP" family of pesticides while in the mother's womb had lower IQs when they reached school age than unexposed children.

But organophosphates aren't the only troublesome pesticides. Other health problems that have been linked to low-dose exposure to these and other pesticides include increased rates of ADHD in children, cancer and Parkinson's disease.

Here's a rogue's gallery of some of the most worrisome, widely used ones:

Chlorpyrifos:

One of the OP pesticides most heavily used by chemical agriculture is chlorpyrifos, also known by the brand names Dursban and Lorsban. It's applied to a number of crops, including corn, oranges and apples. It was once heavily used as an in-home insecticide, but the Environmental Protection Agency banned it for home use in 2001 because of the risk to children's health.

Most recently, chlorpyrifos was back in the headlines when it was listed as a suspect in the mysterious deaths in Thailand of five tourists and a guide, who may have been poisoned by pesticides used to eradicate bedbugs from hotel rooms.

None of this seems to matter to sprayers and manufacturers, though. In the face of this and plenty of other evidence that chlorpyrifos exposure can cause serious and permanent health problems in humans, the statements of leading agribusiness representatives reveal their true colors:

"CAFA (California Alfalfa and Forage Association) has been working hard to oppose some people in the environmental movement who are trying to basically take all the organophosphates away from us, but in particular, chlorpyrifos." - Philip Bowles, CAFA board member and president of Bowles Farming in Los Banos, Calif. Western Farm Press, January 17, 2009

"Chlorpyrifos has become a major target of environmental groups who are trying to take it off the market. Fortunately, Dow AgroSciences has stated its determination to defend the insecticide." - Aaron Keiss, Feb.18, 2010 column in Western Farm Press

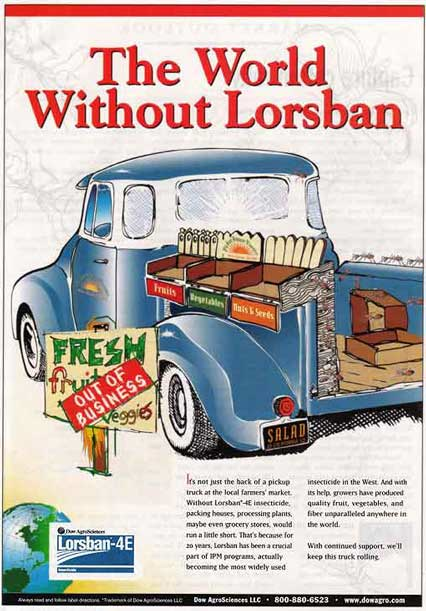

When environmental and community groups pressed EPA to restrict Lorsban, one of Dow AgroSciences' popular organophosphate products, the company ran this ad depicting a world without fruits and vegetables.

The environmental group EarthJustice responded on July 22, 2010, with the story of what happened to the family of Luis Medellin, a resident of California's Central Valley, when chlorpyrifos was sprayed on orange groves near their home.

"Medellin lives with his parents and three little sisters in the agricultural town of Lindsay, California, where chlorpyrifos is sprayed routinely on the orange groves surrounding his home. During the growing season, the family is awakened several times a week by the sickly smell of nighttime pesticide spraying. What follows is worse: searing headaches, nausea, vomiting."

Tests showed that Medellin had five times more chlorpyrifos in his body than the average American, based on research conducted by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The next day, an article in the San Francisco Chronicle, quoted Cynthia Cory, director of environmental affairs for the California Farm Bureau Federation, as having this to say about chlorpyrifos and the situation the Medellin family faced:

"We have to continually evaluate chemicals and make sure they are used in the safest way - but I do believe that has been done with this chemical. It's a widely used chemical in California and across the United States, and it's used on a wide range of insects. There's no alternative that's going to replace it tomorrow, but we try to continue to reduce its use."

Think about it. If chlorpyrifos is so safe, why does chemical agriculture strive to reduce its use?

Parathion:

One of the most notorious organophosphates is parathion, which made hundreds, if not thousands, of farm workers sick and was responsible for nearly 100 deaths before it was banned in the U.S. in 2003. More than a decade earlier, public health officials and agribusiness executives had been debating its risks to human health.

"It is a chemical that is very acutely toxic, and as an agency we need to decide what we are going to do on it quickly." - Linda J. Fisher, then EPA's assistant administrator in charge of pesticides, in March 1991.

But according to a story by Maura Dolan in the Los Angeles Times at the time, the toxicity of parathion was hardly atop the list of concerns for Bob Krauter of the California Farm Bureau.

"Bob Krauter, spokesman for the California Farm Bureau, said the loss of the pesticide, manufactured by Cheminova A/S, a Danish company, would be especially hard for almond growers, the farmers most dependent upon it in California. Substitutes tend to be less effective and more expensive, he said."

Krauter's bottom line: Nuts come before the public's health.

Aldicarb:

This pesticide was responsible for the worst outbreak of pesticide poising in U.S. history.

"At least 2,000 people fell ill from eating California watermelons illegally contaminated with aldicarb on the Fourth of July in 1985," wrote Environmental Health News' Marla Cone on Aug. 18, 2010.

Four years later, the EPA began a push to restrict the use of aldicarb, as the New York Times reported on March 21, 1989:

"The Environmental Protection Agency's pesticide division has recommended barring the use of an acutely toxic insecticide on potatoes and imported bananas. The staff report says the chemical presents an unreasonable risk to infants and children.

"One drop of aldicarb absorbed through the skin can kill an adult, toxicologists say.

"A spokesman for Rhone-Poulenc (manufacturer of aldicarb), Mary Anne Ford, said today that aldicarb is not a hazard on food crops.

''That data does not reflect any risk to any group including infants and children,'' said Ms. Ford. ''I'm concerned for parents who hear such unrealistic numbers.''

Thanks for your concern, Ms. Ford.

Despite toxicity concerns that first surfaced in the 1980s, aldicarb is still being used today. Its U.S. manufacturer, Bayer CropScience, has begun to phase out the chemical and agreed to terminate all uses by 2018, but despite all the misery it has caused farmers and consumers for decades, the company still more or less sticks to the original talking points, as reflected in this August 2010 press release:

"Although the company does not fully agree with this new risk assessment approach, Bayer CropScience respects the oversight authority of the EPA and is cooperating with them. This decision does not mean that aldicarb poses a food safety concern.

"'For nearly 40 years, Temik (aldicarb) has provided farmers with unsurpassed control of destructive pests, without compromising human health or environmental safety,' said Bill Buckner, president and CEO of Bayer CropScience.

"'We recognize the significant impact this decision will have on growers and the food industry, and will do everything possible to address their concerns during this transition,' added Buckner."

What about the impact this pesticide has had on the public's health for more than four decades, Mr. Buckner?

The Public Votes at the Grocery Store

While chemical agriculture clings to its arsenal of pesticides, the American public has become increasingly concerned - and rightly so - about their presence in food. A recent NPR/Thomson-Reuters poll found that nearly 60 percent of Americans prefer organic produce to conventional alternatives, a third them primarily because of pesticide concerns.

The reactions of pesticide users and producers I've highlighted are just a snapshot of the industry's typical response in the face of research and federal action focusing on the negative impacts that pesticides have had on human health.

Its leaders never acknowledge possible risks to people, especially children. Time and again, their only concern is for losing a tool from the pesticide toolbox. That should tell consumers something about where U.S. agribusiness stands on the use toxic chemicals in growing its fruits and vegetables.

|

|

|

|

Copyright 2011 Energy and Technical Services Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Energyts.com |