|

| Reviews and Templates for Expression We |

Why green-minded firms should think like oil companies

Let me start by stating the obvious: The current trajectory of our society's consumption of natural resources is not sustainable. I know it, you know it, NGOs know it, and policy makers and business leaders increasingly know it.

Yet as the world prepares for the Rio+20 Conference on Sustainable Development in June, two questions loom large:

1. Why haven't we made substantive progress towards sustainable development over the last 20 years?

2. What do we need to do differently over the next 20 years to transition to a sustainable economy?

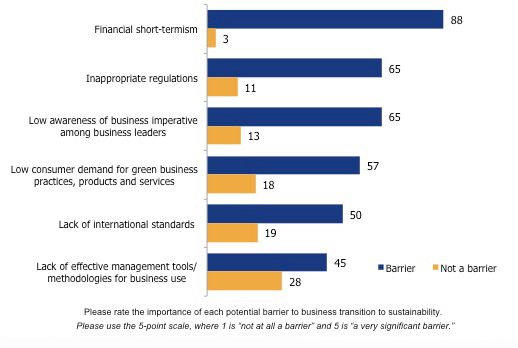

In December 2011, GlobeScan and SustainAbility, in collaboration with UNEP, queried about 650 sustainability experts and practitioners from around the world to get intelligence on the barriers that are impeding progress to sustainability.

The biggest barriers? Financial short-termism, inappropriate regulations and low awareness of the business imperative among business leaders.

The chart below, taken from the survey results, shows why financial short-termism is far and away the greatest barrier to business transition to sustainability.

Let me start by stating the obvious: The current trajectory of our society's consumption of natural resources is not sustainable. I know it, you know it, NGOs know it, and policy makers and business leaders increasingly know it.

Yet as the world prepares for the Rio+20 Conference on Sustainable Development in June, two questions loom large:

1. Why haven't we made substantive progress towards sustainable development over the last 20 years?

2. What do we need to do differently over the next 20 years to transition to a sustainable economy?

In December 2011, GlobeScan and SustainAbility, in collaboration with UNEP, queried about 650 sustainability experts and practitioners from around the world to get intelligence on the barriers that are impeding progress to sustainability.

The biggest barriers? Financial short-termism, inappropriate regulations and low awareness of the business imperative among business leaders.

The chart below, taken from the survey results, shows why financial short-termism is far and away the greatest barrier to business transition to sustainability.

Financial Short-Termism

Sustainability is without a doubt a long-term investment. While some initiatives and actions can have very short-term payback periods, creating lasting and meaningful change both within and beyond an individual organization requires patience, endurance and confidence in measures whose returns are not guaranteed.

In an environment in which investors want to see results quickly, and where investment managers are hired, compensated and fired based on their performance over 6-12 months, it is no wonder that financial short-termism is seen as the most significant barrier to sustainability.

What can businesses do in the face of this market force? Well, perhaps they can act more like oil companies -- yes, I did say oil companies. Here is what I mean.

Oil exploration and production is an activity with long payback periods and uncertain outcomes. Successful exploration companies drill many wells in diverse locations and geologies, and it usually takes years -- and sometimes a decade or more -- for production to come on line. Some wells are dry holes while others are gushers. Technology has dramatically improved "hit rates," but companies still sometimes come up dry.

The most successful companies are willing to make enormous investments, knowing that some wells won't pay out, but the majority will. What's important is not that every well is a gusher but rather the success of the overall portfolio, and the ability to learn from mistakes and apply those learnings to the next well.

Next page: Regulations and international standards

Likewise a "sustainability portfolio" (if you wish to call it that) should include some sure things like lighting upgrades and operational improvements, as well as longer-term, higher risk/higher reward strategies. Not only is it important to think and act for the long term, but it is equally important to communicate for the long term. For example, shifting language from "initiative" to "strategy," and from "spend" to "invest" signal that sustainability is a long-term endeavor given the same level of analysis and rigor as other major business decisions.

Regulations and International Standards

Nearly two-thirds of survey respondents believe that inappropriate regulation -- standards that inhibit, or insufficient rules to encourage, more sustainable practices and behaviors -- constitute a significant barrier to sustainability. Examples may include perverse subsidies, or externalizing the costs of pollution and other environmental impacts.

This is a challenge that can't be fixed by the business community alone. Political posturing, deeply-held beliefs and philosophies about the role of government, national competitiveness, and numerous other dynamics, factor into the development of regulations.

However, business can play a constructive role. As I pointed out in an August 2011 responsible lobbying is not an oxymoron. Business's ability to influence policy-makers -- often maligned as lobbying for "special interests" -- can be deployed to create policies and regulations that encourage, rather than discourage, sustainable business practices. Last summer Ford and others in the auto industry received accolades for advocating for rather than against strict new fuel economy regulations in the US. And in 2009 Apple, Pacific Gas & Electric and several other companies got kudos for resigning from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce over that organization's policy on climate change, which was seen as contrary to the companies' own positions.

Interestingly, only 50 percent of respondents indicated that a lack of international standards is a barrier to sustainability. So while there is much hand-wringing about the failure of the international community to achieve a binding agreement on climate change, experts in this survey see this as a relatively less important factor for businesses' transition to sustainability.

Low awareness of the business case

Nearly two-thirds of survey respondents also indicated that low awareness of the business imperative of sustainability among business leaders is a significant barrier. But how do we reconcile that with the 2010 Accenture survey that found 93 percent of corporate CEOs believed that sustainability issues will be critical to the future success of their business? Well, perhaps it depends on how one defines sustainability. If it is continuous incremental improvement of environmental impacts plus a dollop of philanthropy, as I believe many CEOs think of sustainability, then the business imperative is indeed widely understood. But if it is to create a business which does not compromise the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (i.e. to transition to a green economy), then low awareness of the business imperative is a significant barrier. If executives truly understood the risks and the opportunities that such issues as human rights, climate change and water scarcity represent to their business, the level of resource commitment -- and consequently the pace of change -- would be dramatically higher than it actually is.

Changing the path

Business leaders understand that our society cannot continue indefinitely on the consumption path we are on. However, many feel constrained by the expectations of shareholders and regulations that disincentivize taking the steps required to begin the transition. The key, of course, is to pursue both the long and short term measures, the tactical and the strategic, the sure things and the big bets. While transformation may occur incrementally, it won't happen at all without seeing and believing in a future economy that is sustainable.

Financial Short-Termism

Sustainability is without a doubt a long-term investment. While some initiatives and actions can have very short-term payback periods, creating lasting and meaningful change both within and beyond an individual organization requires patience, endurance and confidence in measures whose returns are not guaranteed.

In an environment in which investors want to see results quickly, and where investment managers are hired, compensated and fired based on their performance over 6-12 months, it is no wonder that financial short-termism is seen as the most significant barrier to sustainability.

What can businesses do in the face of this market force? Well, perhaps they can act more like oil companies -- yes, I did say oil companies. Here is what I mean.

Oil exploration and production is an activity with long payback periods and uncertain outcomes. Successful exploration companies drill many wells in diverse locations and geologies, and it usually takes years -- and sometimes a decade or more -- for production to come on line. Some wells are dry holes while others are gushers. Technology has dramatically improved "hit rates," but companies still sometimes come up dry.

The most successful companies are willing to make enormous investments, knowing that some wells won't pay out, but the majority will. What's important is not that every well is a gusher but rather the success of the overall portfolio, and the ability to learn from mistakes and apply those learnings to the next well.

Next page: Regulations and international standards

Likewise a "sustainability portfolio" (if you wish to call it that) should include some sure things like lighting upgrades and operational improvements, as well as longer-term, higher risk/higher reward strategies. Not only is it important to think and act for the long term, but it is equally important to communicate for the long term. For example, shifting language from "initiative" to "strategy," and from "spend" to "invest" signal that sustainability is a long-term endeavor given the same level of analysis and rigor as other major business decisions.

Regulations and International Standards

Nearly two-thirds of survey respondents believe that inappropriate regulation -- standards that inhibit, or insufficient rules to encourage, more sustainable practices and behaviors -- constitute a significant barrier to sustainability. Examples may include perverse subsidies, or externalizing the costs of pollution and other environmental impacts.

This is a challenge that can't be fixed by the business community alone. Political posturing, deeply-held beliefs and philosophies about the role of government, national competitiveness, and numerous other dynamics, factor into the development of regulations.

However, business can play a constructive role. As I pointed out in an August 2011 responsible lobbying is not an oxymoron. Business's ability to influence policy-makers -- often maligned as lobbying for "special interests" -- can be deployed to create policies and regulations that encourage, rather than discourage, sustainable business practices. Last summer Ford and others in the auto industry received accolades for advocating for rather than against strict new fuel economy regulations in the US. And in 2009 Apple, Pacific Gas & Electric and several other companies got kudos for resigning from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce over that organization's policy on climate change, which was seen as contrary to the companies' own positions.

Interestingly, only 50 percent of respondents indicated that a lack of international standards is a barrier to sustainability. So while there is much hand-wringing about the failure of the international community to achieve a binding agreement on climate change, experts in this survey see this as a relatively less important factor for businesses' transition to sustainability.

Low awareness of the business case

Nearly two-thirds of survey respondents also indicated that low awareness of the business imperative of sustainability among business leaders is a significant barrier. But how do we reconcile that with the 2010 Accenture survey that found 93 percent of corporate CEOs believed that sustainability issues will be critical to the future success of their business? Well, perhaps it depends on how one defines sustainability. If it is continuous incremental improvement of environmental impacts plus a dollop of philanthropy, as I believe many CEOs think of sustainability, then the business imperative is indeed widely understood. But if it is to create a business which does not compromise the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (i.e. to transition to a green economy), then low awareness of the business imperative is a significant barrier. If executives truly understood the risks and the opportunities that such issues as human rights, climate change and water scarcity represent to their business, the level of resource commitment -- and consequently the pace of change -- would be dramatically higher than it actually is.

Changing the path

Business leaders understand that our society cannot continue indefinitely on the consumption path we are on. However, many feel constrained by the expectations of shareholders and regulations that disincentivize taking the steps required to begin the transition. The key, of course, is to pursue both the long and short term measures, the tactical and the strategic, the sure things and the big bets. While transformation may occur incrementally, it won't happen at all without seeing and believing in a future economy that is sustainable.

|

|

|

|

Copyright 2011 Energy and Technical Services Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Energyts.com |